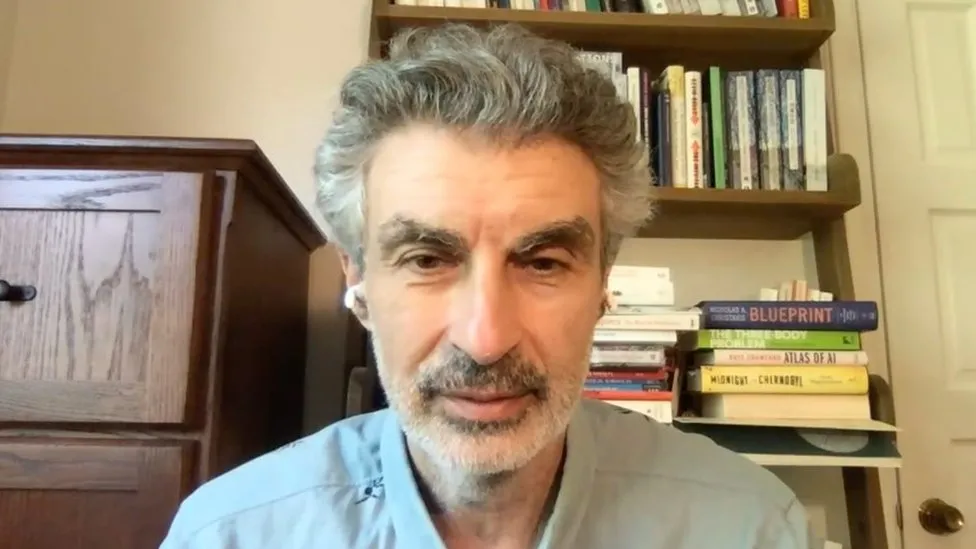

AI 'godfather' Yoshua Bengio feels 'lost' over life's work

One of the so-called "godfathers" of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has said he would have prioritised safety over usefulness had he realised the pace at which it would evolve.

Prof Yoshua Bengio told the BBC he felt "lost" over his life's work.

The computer scientist's comments come after experts in AI said it could lead to the extinction of humanity.

Prof Bengio, who has joined calls for AI regulation, said he did not think militaries should be granted AI powers.

He is the second of the so-called three "godfathers" of AI, known for their pioneering work in the field, to voice concerns about the direction and the speed at which it is developing.

In an interview with the BBC, Prof Bengio said his life's work, which had given him direction and a sense of identity, was no longer clear to him.

"It is challenging, emotionally speaking, for people who are inside [the AI sector]," he said.

"You could say I feel lost. But you have to keep going and you have to engage, discuss, encourage others to think with you."

The Canadian has signed two recent statements urging caution about the future risks of AI. Some academics and industry experts have warned that the pace of development could result in malicious AI being deployed by bad actors to actively cause harm - or choosing to inflict harm by itself.

Fellow "godfather" Dr Geoffrey Hinton has also signed the same warnings as Prof Bengio, and retired from Google recently saying he regretted his work.

The third "godfather", Prof Yann LeCun, who along with Prof Bengio and Dr Hinton won a prestigious Turing Award for their pioneering work, has said apocalyptic warnings are overblown.

Twitter and Tesla owner Elon Musk has also voiced his concerns.

"I don't think AI will try to destroy humanity but it might put us under strict controls," he said recently at an event hosted by the Wall Street Journal.

"There's a small likelihood of it annihilating humanity. Close to zero but not impossible."

Prof Bengio told the BBC all companies building powerful AI products needed to be registered.

"Governments need to track what they're doing, they need to be able to audit them, and that's just the minimum thing we do for any other sector like building aeroplanes or cars or pharmaceuticals," he said.

"We also need the people who are close to these systems to have a kind of certification... we need ethical training here. Computer scientists don't usually get that, by the way."

But not everybody in the field believes AI will be the downfall of humans - others argue that there are more imminent problems which need addressing.

Dr Sasha Luccioni, research scientist at the AI firm Huggingface, said society should focus on issues like AI bias, predictive policing, and the spread of misinformation by chatbots which she said were "very concrete harms".

"We should focus on that rather than the hypothetical risk that AI will destroy humanity," she added.

There are already many examples of AI bringing benefits to society. Last week an AI tool discovered a new antibiotic, and a paralysed man was able to walk again just by thinking about it, thanks to a microchip developed using AI.

But this is juxtaposed with fears about the far-reaching impact of AI on countries' economies. Firms are already replacing human staff with AI tools, and it is a factor in the current strike under way by scriptwriters in Hollywood.

"It's never too late to improve," says Prof Bengio of AI's current state. "It's exactly like climate change.

"We've put a lot of carbon in the atmosphere. And it would be better if we hadn't, but let's see what we can do now."

-bbc