Campaign Funding: Will Parties Stay Within Limits?

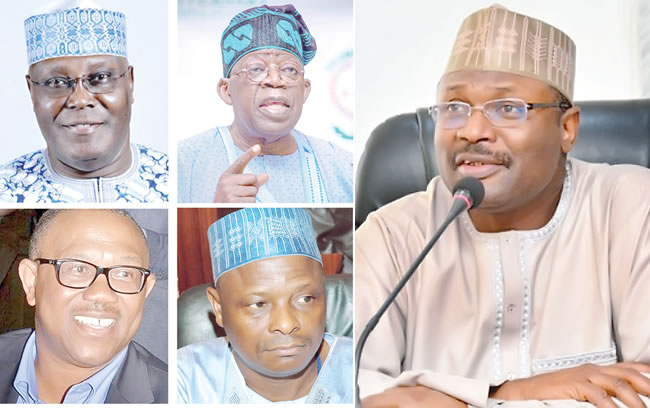

A month after the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) lifted the suspension of campaigns, majority of the political parties and their candidates for the 2023 general elections are still testing waters ostensibly slowed down by the huge logistics required to run a four-month electioneering across the country. Wale Akinselure examines the challenges of campaign funding vis-a-vis the mechanism to ensure compliance with relevant electoral Act.

Even before independence, there were no clear laws regarding party finance and funding. The 1959 elections were conducted with no clearly defined regulatory framework on party finance and the funding of political parties was predominantly through private funding as parties and candidates were responsible for election expenses. During the Second Republic (1979-1983), it was a combination of private and public funding. Government, then, rendered financial assistance to parties by way of subventions. Private funding, except from outside Nigeria, was allowed, and there was no limit on how much corporate bodies and individuals could contribute to parties. The 1979 and 1983 elections were such that parties and politicians had unrestricted freedom to use money from both legal and illegal sources to finance their campaigns and other activities associated with their election expenses. Politicians attached much importance to money which they used to buy the votes of the electorates.

Nigerians have consistently expressed worries about party funding. According to the report of the Political Bureau on the national debate on the political future of Nigeria, Nigerians among other things expressed concerns about the administration and funding of political parties especially the seemingly freedom of limitations on political parties with respect to party funding during the 1979-1983 elections.

In various discourses regarding the challenges facing the country, lack of enabling laws is usually considered as a non-factor. Rather, lack of the political will to implement existing laws or the need to modify the laws to accommodate evolving realities are often identified as the main problem. Among others, an aspect of the nation’s democratic experience that Nigerians have yearned for improvement is enabling laws to improve the electoral process. The yearning is fuelled by the fact that the process has since the first one in 1922 been characterised by issues bordering on imposition of candidates, rigging, thuggery, stuffing of ballots, snatching of ballot boxes, falsification of election result, violence along with other electoral practices. New forms of electoral fraud and corruption have even evolved in the nation’s electoral process since re-emergence of democracy in 1999 with vote buying and massive monetization of politics as the burdensome challenges towards having a truly people-elected government emerging from an election. There are also the other factors undermining competitive electoral politics like “do-or-die” posture of some politicians, “winner-takes-all” philosophy, huge level of poverty and illiteracy, absence of clear ideological underpinning of the parties, religious bigotry, ethnic chauvinism, political corruption and delay in electoral justice.

Just after the 2019 general election, civil societies organisations noted that the election was characterised by violence, voter intimidation, ballot stealing, apathy, over militarisation, abuse of process by officials of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). Almost for every electoral cycle, laws are modified towards addressing the challenges and having an election where people’s sovereignty in choosing their leadership is not subverted. After the 2023 elections, stakeholders observed that the laws to do not effectively regulate the campaign expenditures of individual candidates contesting elections, though the laws require INEC to exercise control over political campaign expenditures. Section 225 (2) of the 1999 Constitution specifically requires the parties to disclose their sources of funds and manner of expenditures. However, stakeholders, then, observed that it may be difficult for INEC to fully monitor where parties and their candidates draw campaign funds from. Calls were then made on the commission to device ways and means of implementing the reporting, disclosure of all monies and assets received by the parties in aid of their campaign effort.

During an INEC-Civil Society Forum Society seminar on November, 27, 2003, former President Olusegun Obasanjo also pointed to the dangers associated with uncontrolled use of money for elections. Likening the cost expended on elections to that spent on war, Obasanjo said: “Even more worrisome, however, is the total absence of any controls on spending by candidates and parties towards elections. I have said that we prepare for elections as if we are going to war, and l can state without hesitation, drawing from my previous life, that the parties and candidates together spent during the last elections, more than would have been needed to fight a successful war. The will of the people cannot find expression and flourish in the face of so much money directed solely at achieving victory. Elective offices become mere commodities to be purchased by the highest bidder, and those who literally invest merely see it as an avenue to recoup and make profits. Politics becomes business, and the business of politics becomes merely to divert public funds from the crying needs of our people for real development in their lives.”

After the 2019 elections, top in the call of stakeholders is that the Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill passed by the National Assembly and declined by the President, should be re-introduced, passed by the National Assembly and transmitted to the president for assent. The yearn for amendment to the existing law was because, overtime, campaign funds do not only exceed the limit set by the electoral legal framework but also their sources and how they are utilized are not fully disclosed.

The fact that the limit is mostly exceeded usually creates an uneven playing field, thereby reducing the chances of those who can’t afford the huge cost of campaigns. In fact, the financial requirements of campaign for political parties and candidates go higher election after election.

The parties seem to have turned a blind eye to provisions of the Electoral Act and the 1999 constitution (as amended).After much back and forth, President Muhammadu Buhari, on February 25, 2022, signed into law the Electoral Act Amendment Bill, 2022. Among others, section 85 of the law stipulates that: “Any political party that holds or possesses any fund outside Nigeria in contravention of section 225 (3) (a) of the Constitution, commits an offence and shall on conviction forfeit the funds or assets purchased with such funds to the Commission and in addition may be liable to a fine of at least N5,000,000. A political party shall not accept any monetary or other contribution which is more than N50,000,000 unless it can identify the source of the money or other contribution to the Commission.”

In setting election limits, section 88 of the Electoral amendment law stipulates that the maximum election expenses to be incurred by a candidate at a presidential election shall not exceed N5billion; N1billion for governorship election; N100 million for Senatorial election and N70million for House of Representatives contest. For State Assembly election, the maximum amount of election expenses to be incurred by a candidate should not exceed N30, 000,000 same as chairmanship election to an Area Council while in the case of Councillorship election to an Area Council, the maximum amount of election expenses to be incurred by a candidate should not exceed N5, 000,000.

- Daily Tribune