Delhi's earliest crimes revealed by 1800s police records

On a cold January night in 1876, two weary travellers knocked at Mohammed Khan's house in Delhi's Sabzi Mandi - a thriving labyrinth of narrow alleys in India's capital - and asked if they could stay the night.

Khan graciously decided to let the guests sleep in his room. But the next morning, he found that the men had disappeared. Also missing, was Khan's bedroll which he had given the men to rest. Khan had been robbed, he realised, in a way like no other.

Nearly 150 years on, the story of Khan's ordeal now features in a list of the earliest crimes reported in Delhi, records for which were uploaded on the city police's website last month.

The "antique FIRs" provide details into some 29 other similar cases that were registered at the city's five main police stations - Sabzi Mandi, Mehrauli, Kotwali, Sadar Bazar and Nangloi - between 1861 to the early 1900s. In Khan's case, the police caught the men and sent them to three months in jail on charges of theft.

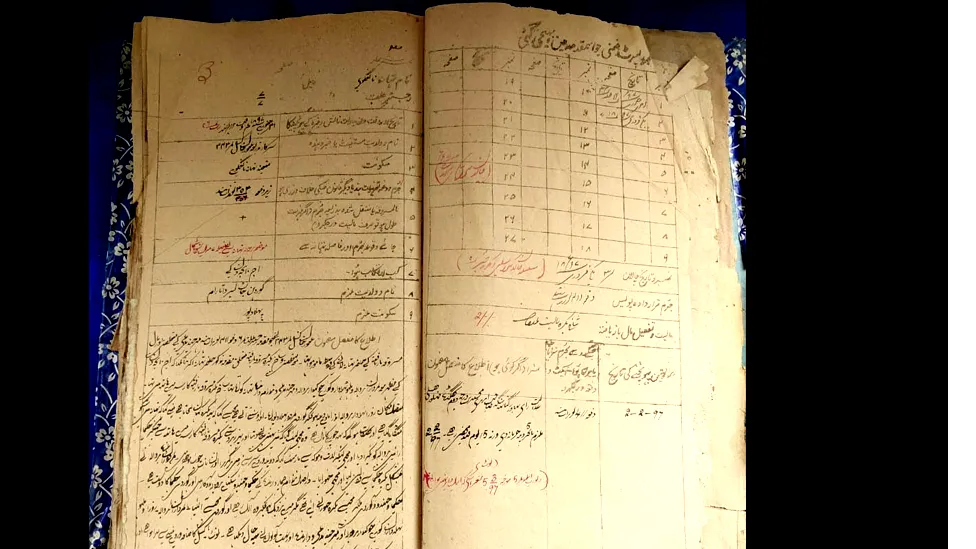

Originally filed in the tenacious Urdu shikastah script - which also has words in Arabic and Persian - the FIRs were translated and complied by a team led by Assistant Commissioner of Delhi Police Rajendra Singh Kalkal, he also illustrated each of the cases himself.

Mr Kalkal told the BBC the records "spoke to him" because of the fascinating insights they offered into the lives of people in a city which has survived waves of conquests and change. "The files are a window to the past as well as the present," he says.

Most of the complaints involve petty crimes of theft - of stolen oranges, bedsheets and ice cream - and carry a comical lightness to them. There's a gang of men who ambushed a shepherd, slapped him and took away his 110 goats; a man who nearly stole a bedsheet but got caught "at a distance of 40 steps"; and the sad case of Darshan, the guardian of gunny bags, who gets beaten black and blue by thugs before they snatch his quilt and a shoe - just one of the pair - and run away.

For anyone familiar with India's past, this might seem odd given how the 1860s was a particularly grim period in Delhi's history. The Mughal rule had just ended after the British suppressed the revolt of 1857, often referred to as India's first war of independence. The city - once an idyll of pleasure gardens, Sufi devotion, arts and Mughal regalia - now laid in ferment, sacked and looted.

Artist and historian Mahmood Farooqi says that one possible reason why no serious crimes occurred at that time was that people had become deeply intimidated by the British, who continued to run a an iron-fisted rule in the years after the revolt.

Men, women and children were brutally massacred. Many were forced to leave Delhi forever and move to the surrounding countryside, where they lived the remaining years in abject poverty. And a few of those, who managed to remain within the city walls, had to live under the constant threat of getting shot or being hanged to the gallows. "This was a time of carnage. People were terrorised and brutalised so much that they bore its trauma for years."

The Indian peasants who fought British rule

Mr Farooqui adds that unlike other cities such as Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) where modern policing had already taken shape, Delhi continued to run on a unique, "a purana, or old" system of policing, laid under the Mughal rule, which was hard to dismantle and replace completely. "So discrepancies or gaps in records are not entirely out of question."

The records, which lie in the Delhi Police Museum, were discovered sometime last year. Mr Kalkal, who was in-charge of the research and preservation of the museum's artefacts, said he found them while he was browsing through the musty old archives one fine day. "I saw hundreds of FIRs lying in obscurity. When I read them I realised how its format has remained unchanged even after 200 years."

Mr Kalkal says he too was struck by the innocuous nature of the offences, a time when stealing objects like cigars, pyjamas and oranges was "the worst imaginable thing".

But the fact that relatively benign crimes were being reported to the cops does not necessarily mean that a lot of heinous crime weren't already happening - Mr Kalal suspects the first case of homicide would've surfaced as early as 1861 itself, when an organised form of policing was established by the British under the Indian Police Act.

"Finding murder cases was not the focus of our research but I am sure they are there, somewhere," he says.

In many complaints, the outcome of the case is marked as "untraceable", suggesting that the culprit was never caught. But in several other, such as Khan's case, swift punishment appears to have been delivered with severity ranging from whippings, beating with canes to a few odd weeks or months of jail time.

One such crime took place at the city's most graceful grande dame, the 233-room Imperial Hotel, in 1897. A chef from the hotel was sent to the Sabzi Mandi police station with a "complaint letter in English" stating that a band of thieves, in an act of unimaginable travesty, had nicked a liquor bottle and a pack of cigars from one of the rooms. The hotel announced a handsome reward of 10 rupees for catching the men. But the case turned cold and could never be solved.

"Today, crimes have become so sophisticated that it takes months and years to solve them. But life was much simpler back then, you either cracked a case or didn't," Mr Kalkal says.

Mr Kalkal's team couldn't be happier about the compilation but he says the initial process of translation was hardly delightful. The difficulty of reading the Urdu shikasta script wore him down on multiple occasions and for cracking that, his team had to seek the skill and persistence of Urdu and Persian scholars and maulvis brought in from every corner of the city.

"But we always knew the effort was worth it," he says.

He was particularly charmed by one passage which described a police officer's annoyance after he was forced to park his "vehicle" - his beloved horse - out in the heat while investigating a theft case.

"The details really make you wonder how far we've come, isn't it?"

-bbc