Emergency alert: Millions receive message and alarm but test failed to send to some mobile users

Once fully up and running, the emergency alerts are designed for use in crises like extreme weather, flooding, and wildfires.

Tens of millions of mobile phone users have received a message and loud alarm during the first nationwide test of the government's new public alert system.

However, many people received the alert at 2.59pm on Sunday, a minute earlier than planned, and others claimed they didn't receive anything until 10 minutes later - or at all.

And in Wales, the government made a spelling error in the translation of the alert sent out in the Welsh language.

A spokesperson for mobile phone network said it was aware that some customers had not received the alert.

"We are working closely with the Government to understand why and ensure it doesn't happen when the system is in use," a spokesman said.

The Cabinet Office said it would be review the outcome of the UK-wide test and acknowledged that a "very small proportion of mobile users on some networks did not receive it".

A UK government spokesman said: "We have effectively completed the test of the UK-wide Emergency Alerts system, the biggest public communications exercise of its kind ever done.

"We are working with mobile network operators to review the outcome and any lessons learned."

Alert test

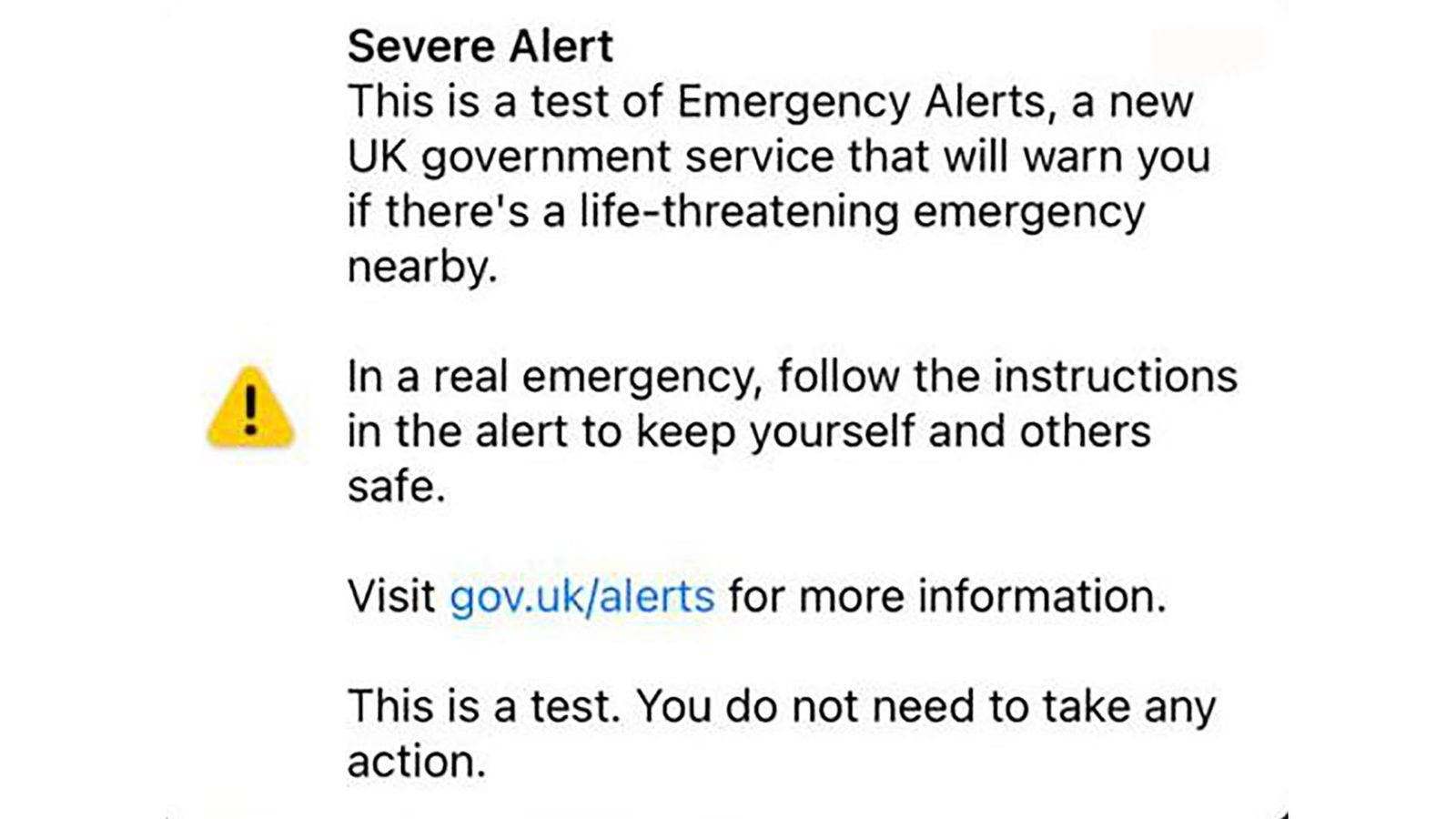

The distinct sound and vibration was accompanied by a message telling people about the service, which is designed to warn if there is a life-threatening emergency nearby.

The 10-second alert was sent to every 4G and 5G device across the UK. People were told that they did not have to take action, and could swipe the message away.

According to the government guidance, people would not receive alerts if their phones were turned off or in airplane mode; if they were connected to a 2G or 3G network; if they were only connected to wifi; or if their phones were not compatible.

Ministers hoped the test would get the public used to what the alerts look and sound like, should they need to be sent during any future crises.

It is intended to be used in situations such as extreme weather, flooding, and fires.

Deputy Prime Minister Oliver Dowden said "it really is the sound that could save your life".

But critics have said the alerts themselves could put people's safety at risk, including drivers who may become distracted and domestic violence victims who keep a secret phone.

Ahead of Sunday's test, sports stadiums, theatres, and cinemas were among those planning how to guard against disruption when it went off.

The emergency alerts are broadcast via mobile phone masts and work on all 4G and 5G phone networks.

That's different to how the government sent out lockdown orders during the pandemic, when SMS messages were sent directly to phone numbers.

It means whoever sends an alert does not need your number, so it's not something you need to reply to, nor will you receive a voicemail if you miss it. No location or other data will be collected, either.

It also means alerts could be sent to tablets and smartwatches on their own data plans.

Anyone in the range of a mast will receive an alert, and they can be tuned based on geography - for example, Manchester residents would not need an alert about life-threatening flooding in Cornwall.

Ministers have insisted alerts will only be sent in "life-threatening" situations.

People who do not wish to receive the alerts will be able to opt out in their device settings, switch off their phones, or place them in flight mode - but the authorities hope many will choose to keep them on.

Such systems have seen increased adoption by governments in recent years, with the pandemic and climate-related emergencies increasing the need for fast and direct communication with the public.

The EU has introduced a directive requiring member states to have a phone-based public warning system.

-sky news