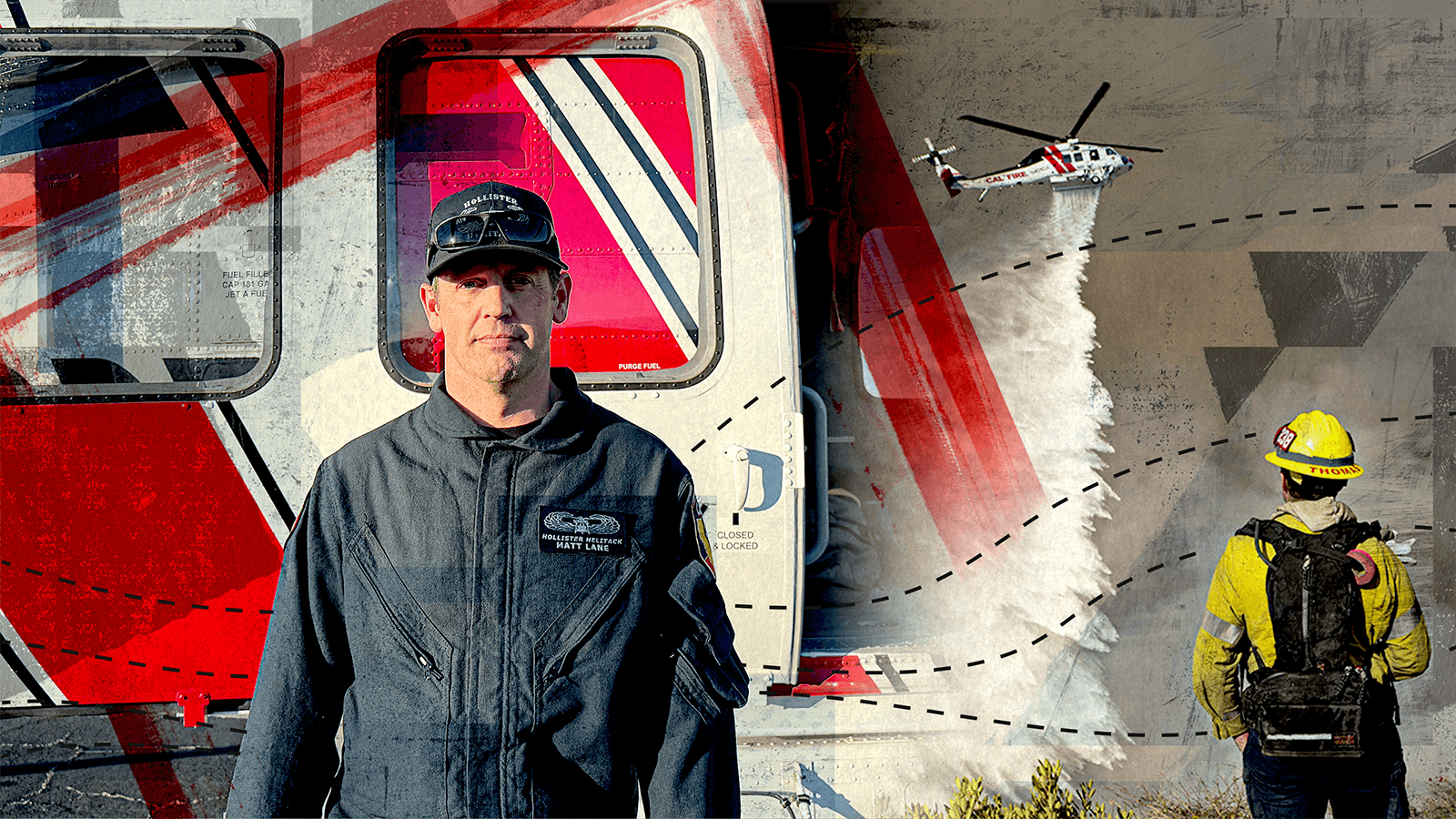

Fighting LA’s fires from the sky

The helicopter team saving lives and homes

For more than a week, the skies above Los Angeles have buzzed with helicopters, aeroplanes, and drones battling the most devastating fires in southern California history.

Helicopters in particular - able to drop vast volumes of water precisely and fly at night - have helped turn the tide against the wind-fuelled infernos that have killed at least 27 people and devoured thousands of buildings.

The two largest fires, Eaton and Palisades, are still burning across a combined total of about 40,000 acres.

Many of the choppers hurtling back and forth over LA belong to Cal Fire, the government agency tasked with protecting California from these disasters.

For the pilots and helicopter teams - dropping water, refuelling, and working tirelessly to avoid crashes and burnout - the past 11 days have been career-defining and physically gruelling.

Taking part in one of the most ambitious aerial assaults on a wildfire ever seen, Cal Fire’s team have pioneered new tactics and learned lessons they hope will help others fighting the increasing numbers of wildfires globally.

This is their story.

When a blaze fuelled by hurricane-force winds broke out in the Palisades on 7 January, Cal Fire joined an unprecedented operation to stomp it out made up of the National Guard, the city of Los Angeles and other private firefighting companies.

In the early hours of the fires, powerful winds made it too dangerous to fly. As soon as the winds slowed enough, aerial firefighters joined the fray and never let up.

From a swiftly assembled helicopter base at Camarillo Airport about 40 miles west, Cal Fire set about flying missions 24-hours a day, pummelling the Palisades Fire with hundreds of thousands of gallons of water dropped from specially outfitted helicopters known as Firehawks.

The Cal Fire helicopter team had one job: slow down the fire so that their fellow firefighters on the ground could successfully contain the blaze. It is a task that their helicopters are perfectly engineered to perform.

In the mountains and canyons of the Palisades region, the helicopters can swoop through the melee and get as close to the flames as possible.

Matt Lane, a fire captain, took to the skies for hours of intense firefighting.

“It was a very heavy firefight, one of the busiest airspaces I've ever been a part of... very windy conditions, a lot of rapid fire spread. A lot of structures being threatened,” he said.

By Wednesday 8 January, the fire in Pacific Palisades had exploded from 10 acres to more than 2,900 acres.

It’s a 10 minute flight from Camarillo Airport, the main staging area for the helicopters, to Los Angeles. Crews sped back and forth, scooping up water from the Encino reservoir and dropping it repeatedly to try to stem the fire’s advance.

At sunset on 8 January, one of Cal Fire's Firehawk helicopters - "Copter 602" - heads to the ocean to fill its water tanks before approaching the Palisades Fire in the hills around Eastern Malibu.

As the fire spreads, another run takes them further east to the front around Encino and Mandeville Canyon. They spend almost an hour in the area, using Encino reservoir to fill tanks for fresh runs to tackle the blaze.

Flight paths of the helicopters - of which we have plotted only one of many - shows the Firehawk crew makes five loops from the ocean at Malibu to the nearby fire before returning to base.

By the end of the day, two people had died in a new fire that started near Altadena, almost 70,000 people were under evacuation orders and the emergency services were stretched to the limit.

Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass declared a state of emergency.

The drop

Years of training and practice go into the split-second decisions required to drop water accurately on a target.

“It’s so complex with different wind speeds and altitudes that pilots just have to kind of work it out, and we work together as a flight crew,” said Lane. “A little left, a little right, let’s adjust a little bit.”

“Eventually the science kind of goes out the window and it becomes an art,” he said.

As it prepares to make a run, an S-70i Firehawk, like the one Lane flies every day, will hover over a water source that can be as shallow as 18 inches.

Co-ordinating helicopters then help guide the Firehawk helicopters to their drop.

Sometimes, unfortunately, they miss.

“It sucks! Missing sucks! It’s no fun,” said Lane. But when they manage to drop water precisely on their target, it’s as gratifying as you might think.

“It feels good, it feels like we're being effective,” Lane said.

Cal Fire has run a full scale night operation to battle the Palisades blaze - an unprecedented undertaking for the agency.

They can do this because of specially equipped helicopters that can fly missions in the dark. Some of the Firehawks are fitted with night equipment, as is a Bell 429 helicopter and similar aircraft that the co-ordinators use to direct the firefight.

"Here's the fun thing at night: when you get to drop water on fire, compared to the day, you actually visibly, visually see the fire go out,” said Paul Karpus, Cal Fire division chief for tactical air operations on the Palisades fire.

But flying missions at night is especially taxing, say the people who have battled the Palisades blaze in the dark.

“It’s very fatiguing with the goggles down, your focus is limited and your concentration is more [intense],” said John Williamson, a fire captain who co-ordinates night missions. “It’s more of a brain fatigue.”

Video taken from one of the helicopters on 10 January at about 20:00 shows the intensity of their missions.

Because of the strenuous nature of the task, pilots and firefighters who fly at night are limited to five or six-hour shifts.

"I think the night operations did a lot of good," Williamson said. "We were able to turn a lot of corners for folks on the incident. It really made a difference with the amount of resources we had on the night operation."

Buzzing skies

Several agencies, municipalities, and private companies flew in to fight the Palisades fire.

Everything below - from scrubland to houses and cars - is covered with a layer of pink retardant, which helps the ground crews with their task.

All those helicopters and planes descending on a relatively small area makes for some very, very busy airspace.

That’s where Cal Fire captains like Williamson come in.

They hover a thousand feet above the fray in helicopters like the Bell 429. Cal Fire is using versions equipped with multiple AM and FM radios and night vision capabilities.

Digital screens in the cockpit allow the crew see all the other helicopters participating in the firefight. Bright lights illuminate their way at night. The craft is light and nimble, and powered by twin engines.

From up high, they can co-ordinate multiple aircraft to drop their water on the same target, extinguishing the flames for the ground team below.

The Cal Fire team has a particular affection for their Bell 429.

“This is the one I've been on since the beginning,” said Williamson. “It’s awesome. It’s a pretty rad helicopter.”

On Wednesday night, a week after the fire broke out, a fleet of Cal Fire and private helicopters sat glittering in the sunset at the Camarillo helibase as pilots and firefighters changed shifts.

They milled about, drinking coffee and catching up with their fellow firefighters, who had flown in from all over the state to assist Los Angeles. As night fell, they gathered around a detailed map of the Palisades to receive an update on conditions.

So far, the Palisades Fire had consumed nearly 24,000 acres and destroyed more than 2,800 structures. Eight people had died. But the fight seemed to have turned a corner.

With firefighters containing more and more of the Palisades Fire, the Cal Fire helicopter team was preparing for a far quieter evening. Though exhausted, they felt proud of what they accomplished that week.

“Mother Nature is hard to fight sometimes, but I think we were helpful in slowing down the spread and putting the fire out,” said Lane.

-BBC