How chocolate became the winter beverage of choice

As Caramac fans weep over the discontinuation of the sickly treat, and Animal Bars are consigned to the dustbin of childhood nostalgia, maybe take comfort in the fact that chocolate fads come and chocolate fads go. Presumably those mourning the Texan or Spira chocolate bars have managed to move on.

If not, sorrows can be drowned in the epitome of "hygge" - a cup of hot chocolate.

And for us, it is easily achievable by reaching for a sachet or popping to a cafe. But a few centuries ago, only the very wealthy would be able to get their mitts on chocolate - and it would be in liquid form.

The words "hot" and "drinking" were only inserted later, when solid chocolate bars were invented (by Fry's of Bristol) in 1847.

Cacao beans began to reach Europe through Spain from 1585, after the Spanish had colonised the Americas, and a document titled A Curious Treatise of the Nature and Quality of Chocolate was translated from the original Spanish and published in England in 1640.

Two years later a second edition of the document was published by Captain James Wadsworth as "Chocolate, Or an Indian Drinke", reporting that chocolate could be purchased "at reasonable rates" from the bookseller John Dakins in Holborn.

Chocolate had arrived in the capital. And the first chocolate house - advertised as being "run by a Frenchman" - in London opened in 1657 in Queen's Head Alley, near Bishopsgate.

Samuel Pepys mentioned it in his diary entry of Wednesday 24 April 1661: "Waked in the morning with my head in a sad taking through the last night's drink, which I am very sorry for; so rose and went out with Mr. Creed to drink our morning draft, which he did give me in chocolate to settle my stomach".

The popularity of this fancy new drink led to an explosion of associated paraphernalia. George Garthorne, a London silversmith, made the earliest-known silver chocolate pot, or chocolatière, in England in 1685.

To go with this, an implement variously known as a molinet, moulinet, molinillo, moussoir or chocolate mill, was necessary because of the high percentage of cocoa butter meant that vigorous mixing was required.

A stirrer made from a long piece of turned wood with a serrated head was rolled between the palms for a good whisking action. The tall narrow pots had a hole in the lid for splash-free swizzling.

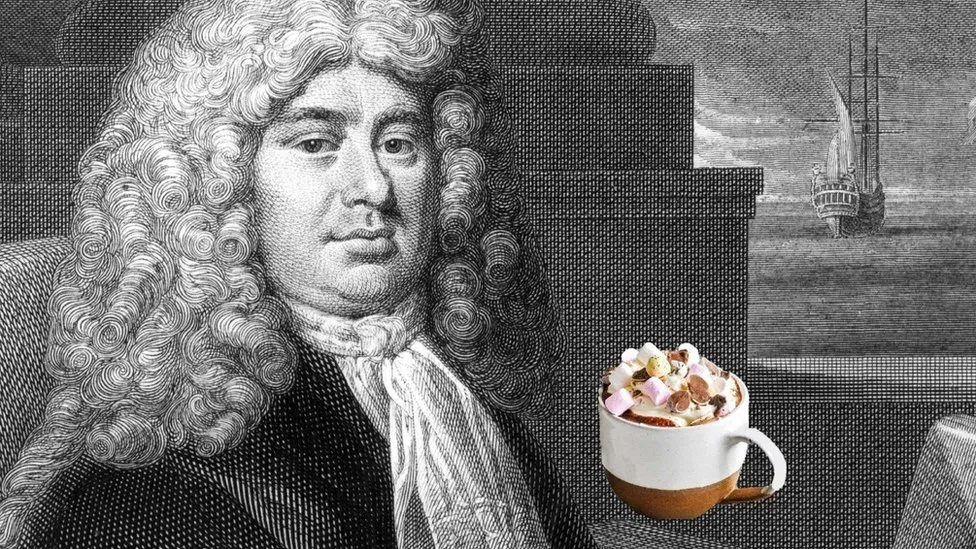

A chocolate pot was even mentioned in Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719, in which the hero left muskets behind on the shipwreck in favour of "a Fire Shovel and Tongs, which I wanted extremely; as also two little Brass Kettles, a Copper Pot to make Chocolate, and a Gridiron".

The 1690s saw the arrival of White's in Mayfair, Saunders's and Ozinda's chocolate houses in St James's Street, and the Cocoa-Tree in Pall Mall. Infused with citrus peel, jasmine, vanilla, musk and ambergris, chocolate was an expensive commodity, and chocolate houses often charged an entry fee.

Writer Jonathan Swift records that one of the meetings of the dining club of which he was a member was held at Ozinda's, and that the meal was brought in from the palace: "Dinner was dressed in the Queen's kitchen and was mighty fine.

"We eat it at Ozinda's Chocolate-house, just by St. James's. We were never merrier, nor better company, and did not part till after eleven."

At White's Chocolate House, the atmosphere was more debauched - to such an extent the establishment, opened at 4 Chesterfield Street in 1693 by Italian immigrant Francesco Bianco, was immortalised in Hogarth's The Rake's Progress, showing a group of men so engrossed in gambling they do not notice the room is on fire.

Rakes Progress

While nowadays a "chocolate kitchen" in one's home might consist of "the kitchen" - or, if fancy, "the kitchen but with a hot chocolate machine" - in the 17th Century, nothing less than a series of rooms was required.

The chocolate kitchen at Hampton Court Palace was built for William III and Mary II in about 1689, and the chocolate room, designed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1690, was just down the cloister from the chocolate kitchen.

It was a secure space, where gilded chocolate pots and expensive chinaware were kept. This is where the chocolate would be poured into ornate receptacles before being conveyed to the king or queen.

King George I went a step further and from 1717 employed his own chocolate maker, Thomas Tosier, at Hampton Court Palace. It was a prized and privileged job - Tosier worked with expensive, exotic ingredients, and had access to the king's bed chamber to serve him his morning drink of chocolate.

Choc drinking

Fashionable rich Londoners, seemingly unable to do anything in a moderate, understated manner, also started to have dedicated chocolate kitchens installed in their homes.

Staff would have to embark on a laborious process of roasting cacao nuts, removing the nibs, grinding the nibs into a paste on a hot stone slab, and forming that paste into blocks (called cakes) which would be left to mature for several months.

The cakes were then melted into milk, water or wine, sweetened with sugar and flavoured with spices.

This time-consuming method of making chocolate meant that it was not a beverage available to the masses - until manufacturing came along. In 1729 a patent was granted by George II for a grinding machine to make finer chocolate powder.

The grantee of that patent was Walter Churchman, who used a water-powered wheel to crush more beans at a time. He moved his company from Bristol to London and produced tablets of chocolate that would dissolve faster than hand-made products.

The business passed into the hands of Joseph Fry and under generations of the Fry family it became the largest commercial producer of chocolate in the UK, until in 1919 it merged with Cadbury's.

And so a cup of chocolate was no longer only in the grasp of wealthy Londoners - although the sweet milky concoction now served bears little resemblance to the fashionable beverage so beloved by the clientele of Whites and its rivals.

Those seeking the authentic, bitter drinking chocolate might be best advised to follow a recipe, such as this from Hannah Glasse's c.1805 cookbook, The - some would argue misnamed - Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.

"Take six pounds of cocoa-nuts, one pound of anise-seeds, four ounces of long pepper, one of cinnamon, a quarter of a pound of almonds, one pound of pistachios, as much achiote (a spice extracted from the seeds of an evergreen shrub) as will make it the colour of brick, three grains of musk and as much ambergrease (alternative spelling of ambergris, a waxy substance formed in the digestive system of a sperm whale), six pounds of loaf sugar, one ounce of nutmegs.

"Dry and beat them, and searce (an obsolete word for sift) them through a fine sieve; your almonds must be beat to a paste, and mixed with the other ingredients; then dip your sugar in orange-flower or rose-water, and put it on a skillet, on a very gentle charcoal fire; then put in the spice, and stew it well together, then the musk and ambergrease, then put the cocoa-nuts last of all, then achiote, wetting it with the water the sugar was dipt in; stew all these very well together, over a hotter fire than before; then take it up, and put it into boxes, or what form you like, and set it to dry in a warm place."

A chocolate kitchen, chocolate serving room, chocolate cloister and full chocolate staff are optional.

-bbc