Middle East conflict: How will it end?

With Israel still reeling from the worst attack in its history and Gaza already under devastating bombardment, it felt like a turning point.

The Israel-Palestine conflict, largely absent from our screens for years, had exploded back into view.

It seemed to take almost everyone by surprise. The US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan had famously declared just a week before the attacks: “The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades.”

A year on, the region is in flames.

More than 41,000 Palestinians are dead. Two million Gazans have been displaced. In the West Bank, another 600 Palestinians have been killed. In Lebanon, another one million people are displaced and more than 2,000 dead.

More than 1,200 Israelis were killed on that first day. Since then, Israel has lost 350 more soldiers in Gaza. Two hundred thousand Israelis have been forced from their homes close to Gaza and along the volatile northern border with Lebanon. Around 50 soldiers and civilians have been killed by Hezbollah rockets.

Across the Middle East, others have joined the fight. Dogged US efforts to prevent the crisis from escalating, involving presidential visits, countless diplomatic missions and the deployment of vast military resources, have all come to nothing. Rockets have been fired from far away in Iraq and Yemen.

And mortal enemies Israel and Iran have exchanged blows too, with more almost certain to come.

Washington has rarely looked less influential.

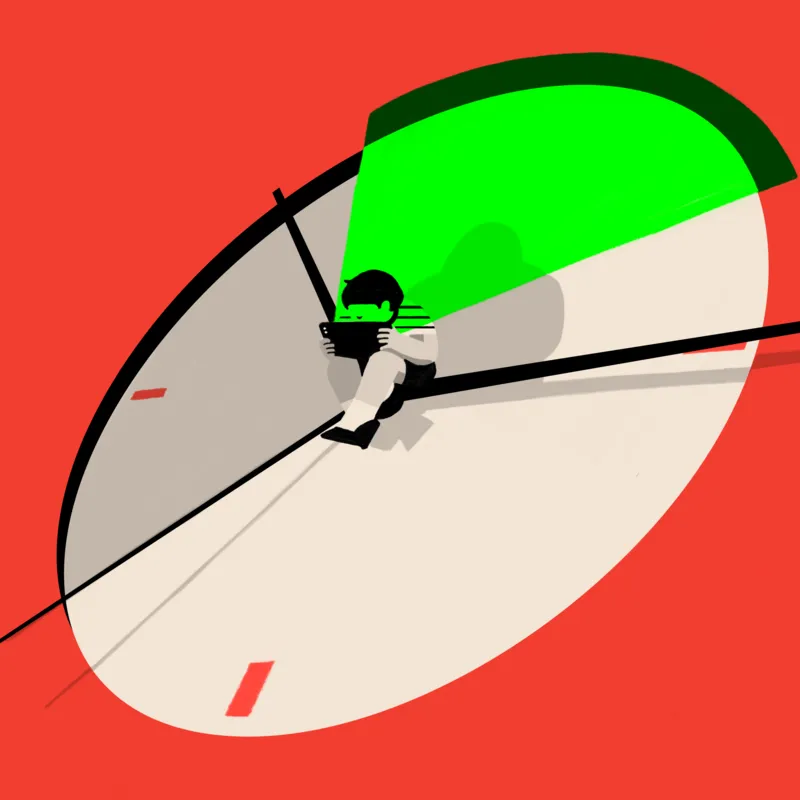

As the conflict has spread and metastasised, its origins have faded from view, like the scene of a car crash receding in the rear view mirror of a juggernaut hurtling towards even bigger disasters.

The lives of Gazans, before and after October 7, have been almost forgotten as the media breathlessly anticipates “all-out war” in the Middle East.

Some Israelis whose lives were turned upside down that terrible day are feeling similarly neglected.

“We have been pushed aside,” Yehuda Cohen, father of hostage Nimrod Cohen, told Israel’s Kan news last week. Mr Cohen said he held Mr Netanyahu responsible for a “pointless war that has pitted all possible enemies against us”.

“He is doing everything, with great success, to turn the event of October 7 into a minor event,” he said.

Not all Israelis share Mr Cohen’s particular perspective. Many now see the Hamas attacks of a year ago as the opening salvo of a wider campaign by Israel’s enemies to destroy the Jewish state.

The fact that Israel has struck back - with exploding pagers, targeted assassinations, long-range bombing raids and the sort of intelligence-led operations the country has long prided itself on – has restored some of the self-confidence the country lost a year ago.

“There is nowhere in the Middle East Israel cannot reach,” Mr Netanyahu confidently declared last week.

The prime minister’s poll ratings were rock bottom for months after October 7. Now he can see them creeping up again. A license, perhaps, for more bold action?

But where’s it all going?

“None of us know when the music is going to stop and where everybody will be at that point,” Simon Gass, Britain’s former ambassador to Iran, told the BBC’s Today Podcast on Thursday.

With a presidential election now just four weeks away and the Middle East more politically toxic than ever before, this doesn’t feel like a moment for bold new American initiatives.

For now, the immediate challenge is simply to prevent a wider regional conflagration.

There’s a general assumption, among her allies, that Israel has the right - even the duty - to respond to last week’s ballistic missile attack by Iran.

No Israelis were killed in the attack and Iran appeared to be aiming at military and intelligence targets, but Mr Netanyahu has nevertheless promised a harsh response.

After weeks of stunning tactical success, Israel’s prime minister seems to harbour grand ambitions.

In a direct address to the Iranian people, he hinted that regime change was coming in Tehran. “When Iran is finally free, and that moment will come a lot sooner than people think, everything will be different,” he said.

For some observers, his rhetoric carried uncomfortable echoes of the case made by American neoconservatives in the run up to the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

But for all the danger of the moment, fragile guardrails do still exist.

The Iranian regime may dream of a world without Israel, but it knows that it’s far too weak to take on the region’s only superpower, especially at a time when Hezbollah and Hamas - its allies and proxies in the so-called “axis of resistance” - are being crushed.

And Israel, which would dearly like to get rid of the threat posed by Iran, also knows that it cannot do this alone, despite its recent successes.

Regime change is not on Joe Biden’s agenda, nor that of his vice president, Kamala Harris.

As for Donald Trump, the one time he seemed poised to attack Iran - after Tehran shot down a US surveillance drone in June 2019 - the former president backed down at the last moment (although he did order the assassination of a top Iranian general, Qasem Soleimani, seven months later).

Few would have imagined, a year ago, that the Middle East was heading for its most perilous moment in decades.

But looked at through that same juggernaut’s rear view mirror, the past 12 months seem to have followed a terrible logic.

With so much wreckage now strewn all across the road, and events still unfolding at an alarming pace, policy makers - and the rest of us - are struggling to keep up.

As the conflict that erupted in Gaza grinds on into a second year, all talk of the “day after” – how Gaza will be rehabilitated and governed when the fighting finally ends – has ceased, or been drowned out by the din of a wider war.

So too has any meaningful discussion of a resolution of Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians, the conflict which got us here in the first place.

At some point, when Israel feels it has done enough damage to Hamas and Hezbollah, Israel and Iran have both had their say - assuming this doesn’t plunge the region into an even deeper crisis - and the US presidential election is over, diplomacy may get another chance.

But right now, that all feels a very long way off.

-BBC