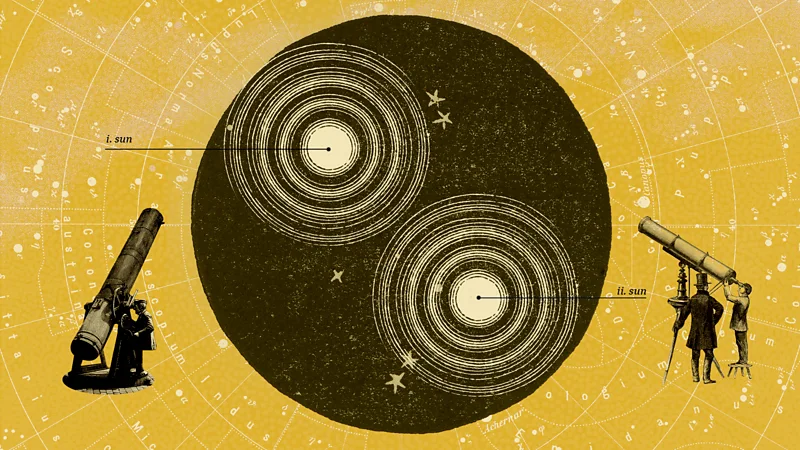

Our Sun may once have had a twin. What happened to this stellar sibling?

Many stars in our galaxy exist in pairs, but our Sun is a notable exception. Now scientists are finding clues that it may once have had a companion of its own. The question is, where did it go?

Our Sun is a bit of an isolated nomad. Orbiting in one of the Milky Way's spiral arms, it takes us on a a journey around the galaxy roughly once every 230 million years on our lonesome. The nearest star to our Sun, Proxima Centauri, is 4.2 light-years away, so remote that it would take even the fastest spacecraft ever built more than 7,000 years to reach.

Everywhere we look in our galaxy however, the star at the centre of our Solar System seems like more and more of an anomaly. Binary stars – stars that orbit the galaxy inexorably linked together as pairs – appear to be common. Recently astronomers have even spotted a pair orbiting in surprisingly close proximity to the supermassive black hole that sits at the heart of the Milky Way – a location that astrophysicists thought would cause the stars to be ripped apart from each other or squashed together by the intense gravity.

In fact, discoveries of binary star systems are now so common that some scientists believe that perhaps all stars were once in binary relationships – born as pairs, each with a stellar sibling. That has led to an intriguing question: was our own Sun once a binary star too, its companion lost long ago?

It's definitely a possibility, says Gongjie Li, an astronomer at the Georgia Institute of Technology in the US. "And it's very interesting."

Fortunately for us, our Sun does not have a companion today. If it did, the gravitational pull of a solar sibling could have disrupted the orbit of the Earth and the other planets, condemning our home to lurches from extreme heat to terrible cold in a way that may have been too inhospitable for life.

The closest binary stars to Earth, Alpha Centauri A and B, orbit each other at about 24 times the Earth-Sun distance, or 3.6 billion miles. Suggestions that our Sun could also have a faint companion circling our Solar System today – a hypothetical star often called Nemesis – have fallen out of favour since they were first proposed in 1984 after no such star was found in multiple surveys and studies.

But when our Sun first formed 4.6 billion years ago, however, it may have been a different matter.

Stars form when giant clouds of dust and gas tens of light-years across cool and clump together. The material inside these nebulae – as these cocoons of gas and dust are known – collapse together under gravity into ever growing lumps. As it does so, it begins to warm up over millions of years, eventually igniting nuclear fusion to create a protostar with a disk of remnant debris spinning around it, which forms planets.

In 2017, Sarah Sadavoy, an astrophysicist at Queen's University in Canada, used data from a radio survey of the Perseus molecular cloud – a stellar nursery filled with young binary star systems – to conclude that the process of star formation might preferentially form protostars in pairs. Indeed, she and her colleagues found it was so likely that they suggested all stars might form in pairs or multi-star systems.

"You get little density spikes within those cocoons, and those are able to collapse and form multiple stars, which we call a fragmentation process," says Sadavoy. "If they're very far away [from each other], they might never interact. But if they're much closer, gravity has a chance to keep them bound together."

Sadavoy's work showed that it was possible that all stars once started as a binary, and while some remain bound together indefinitely, others would break apart rapidly within a million years. "Stars live for billions of years," she says. "It is a blip in the grand scheme of things. But so much happens in that blip."

That raises the question of whether the same might have been true of our Sun. There's no reason to think it wasn't, says Sadavoy. But "if we did form with a companion, we lost it", she says.

It is likely that any companion would now be lost among the sea of stars that we see in the night sky – Sarah Sadavoy

There are some tantalising clues emerging our Sun was once part of a binary system. In 2020, Amir Siraj, an astrophysicist at Harvard University in the US, suggested that a region of icy comets that surrounds our Solar System far beyond Pluto, called the Oort Cloud, might contain an imprint of this companion star. This frigid shell of ice and rock is so far away that the most distant spacecraft ever launched by humankind – Voyager 1 – will not reach it for at least another 300 years. (Read more about what the Voyager missions are teaching us about the weird space on the outskirts of our Solar System.)

If our Sun did have a companion, then it would have resulted in more dwarf planets like Pluto existing in this region, says Siraj. It might also have led to a larger planet ending up here, like the hypothesised Neptune-sized world Planet Nine that some astronomers believe remains undiscovered in our Sun's outer reaches. (Read more about the mystery of Planet Nine in this article by Zaria Gorvett.)

"It's hard to produce quite as many objects in the furthest reaches of the Oort Cloud as we see" without a companion star, says Siraj, with billions or even trillions of objects orbiting in the Oort Cloud. If an additional planet like Planet Nine were to be found, explaining how such a planet ended up so far from the Sun is "really hard", says Siraj, unless we invoke the disrupting gravitational hand of a companion star. "It could boost the capture of comets and the chances of the Solar System capturing a planet," he says.

Konstantin Batygin, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in the US who first proposed the existence of Planet Nine in 2016 based on the clustering of distant objects, isn't so sure about the idea. "A binary companion is by no means required to explain the Oort Cloud," says Batygin. "You can fully explain the existence of the Oort Cloud just by the fact that the Sun formed in a cluster of stars, and as Jupiter and Saturn grew to their present-day masses, they ejected a bunch of objects." Even Planet Nine can be explained just by "passing stars in the birth cluster", he says.

However, in a recently published research paper, Batygin suggests that the inner edge of the Oort Cloud could be explained by a companion star. "What we found by doing computer simulations is that as objects get scattered out, they start to interact with the binary companion," says Batygin. "They can detach from the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn and get trapped in the inner Oort Cloud."

It might be possible to confirm if this idea is true with a new telescope in Chile, called the Vera Rubin Observatory, set to switch on next year and perform the most detailed survey ever of the night sky over the following 10 years. "As Vera Rubin comes online and begins to really map out the structure of the Oort Cloud in greater detail, we can see if there's a clear thumbprint of the binary companion," says Batygin.

Another possible signature of a binary companion's impact is that our Sun is tilted very slightly, by about seven degrees, to the plane of the Solar System. A possible explanation for this is the gravitational pull of another star, which tilted our Sun off balance. "I think the most natural explanation is the presence of a companion star early on," says Batygin, an effect that we see in other binary stars throughout the galaxy.

But even if this early evidence does turn out to be correct, finding our Sun's missing twin may be a far more challenging prospect. It is likely that any companion would now be "lost among the sea of stars that we see in the night sky", says Sadavoy.

However, stars born in the same region of space as our Sun might have a similar composition because they will have been forged from the same mix of gases and dust, making them all veritable siblings. In 2018, scientists identified one such a "twin" star of our Sun, with a similar size and chemical composition located less than 200 light-years away. Before we get too excited, however, it is worth remembering that the cloud of gas and dust in which our Sun was born also probably formed "hundreds or thousands of stars", says Sadavoy. All of these would have a similar composition, meaning there would be no way to know if any were our Sun's true companion. Even then, any companion of our Sun might not have been a similarly sized star. "It could have been a [smaller] red dwarf star, or a hotter, bluer star," says Sadavoy.

While finding and identifying our Sun's possible companion seems daunting, the prospect that it was once a binary star raises interesting implications for planets around other stars, known as exoplanets. Most notably, it would demonstrate that in our Solar System, the existence of life and the survival of our planets was not diminished by the presence of another star. "There are many discovered exoplanetary systems that actually orbit stellar binaries," says Li. Some of those orbit one of the two stars, known as circumstellar systems, while others orbit both of the stars and have skies with two suns like the fictional planet Tatooine in Star Wars. These are called circumbinary systems.

Sometimes we do see binary companions causing havoc with such systems, though. "It depends on how far away the star is," says Li. If the star is closer in, it can "kick the planetary orbits" and push them into eccentric, non-circular shapes. "In circumstellar systems, the planets could have a high eccentricity," says Li. "But this may not necessarily make them unstable." It can, however, cause the planet to experience large changes in temperature as it swings closer to and further from the star, he says.

For our own planet, it seems that the possible existence of a binary companion to our Sun long ago did not hinder our own existence. And as scientists examine the furthest regions of our Solar System in ever more detail, they may well uncover more signs that it once did exist – a lasting signature waiting to be found.

If it does exist it could be out there, somewhere, with a solar system all of its own. "It might not have trailed too far behind or ahead," says Sadavoy. "Or it could be on the other side of the galaxy and we would not know.

"It could be anywhere."

-BBC