Robin Redbreast: The terrifying 'lost' 1970s horror that was Britain's answer to Rosemary's Baby

A little-remembered TV film broadcast on the BBC, Robin Redbreast was a chilling parable – about a single, pregnant woman trapped in a sinister village – that was ahead of its time. Now a new stage adaptation is putting it back in the spotlight.

More than 50 years after its release, The Wicker Man (1973) remains one of the most chilling examples of what has come to be known as folk horror. Roman Polanski's 1968 film Rosemary's Baby remains similarly seminal in the horror genre. Yet another work from around that time, which has been almost forgotten, melded elements of both those classics to terrifying effect – Robin Redbreast, a relatively little-known television film originally broadcast in 1970 as part of the BBC's Play for Today series.

Robin Redbreast was, on the one hand, part of a wave of folk horror produced in the UK in the 1970s, also including Penda's Fen (1974) and The Stone Tape (1972). But uniquely, it also explored issues surrounding women's bodily autonomy with a degree of frankness that still feels bold today. Written by British playwright and novelist John Bowen, it tells the story of a modern single woman, who moves from the city to an unnamed village, falls pregnant, and finds herself the subject of scrutiny from neighbours whose intentions may not be benign.

Now comes a new stage production based on the film, starring and co-created by the actor Maxine Peake, which opens this week in Manchester. "I'd had the idea of doing something in the folk horror genre," Peake explains to the BBC of the project's genesis – but it was the particular mixture of themes and the focus on fertility that drew her back to Robin Redbreast, having first encountered the film back in the 2000s. She has created the play, entitled Robin/Red/Breast, along with the director Sarah Frankcom and the choreographer Imogen Knight, her co-founders of the collective Music, Art, Activism and Theatre (MAAT). "It's raw, it's fleshy, it's visceral. There are a lot of ingredients," she says of the production. It is not a conventional stage adaptation – the audience wears headphones, and sound plays a key role in the show, with music from electronic producer Gazelle Twin and an all-female brass band – but it will, they hope, bring out the original's mix of the sinister and the uncanny.

An exploration of women's fears

The television film was notable for the way it handled its protagonist's pregnancy as both a source of power, connecting her with the land in a primal way, and as a way in which women can be controlled. Following the Supreme Court's repeal of its 50-year-old Roe v Wade decision in the US, and with women's reproductive rights being rolled back in countries like Poland, which has implemented a near-total abortion ban, it's unsurprising that pregnancy is on filmmakers' minds once more. Recent Hollywood horrors The First Omen and Immaculate have centred pregnancy and bodily autonomy as themes, though it is British director Alice Lowe's 2020 film Prevenge that has the most shared DNA with Robin Redbreast, in the way it taps into women's fears – and fears about women. "That's what's so exciting about horror," says Booker-nominated novelist Daisy Johnson, who is working with Peake on the new production. "It can be about one thing while really being about something else entirely. Who owns your baby and who owns your body? That's a real growing fear again."

Produced by Graeme MacDonald, who would go on to be controller of BBC2, Robin Redbreast was broadcast on 10 December 1970. The original colour version has been lost and only a black and white version remains. It focuses on newly single Norah Palmer (played by Anna Cropper, with a mix of pragmatism and dry wit), a cosmopolitan TV script editor, who following a break-up, decides to retreat for a while to the country cottage she bought with her ex. The minute she arrives, it becomes apparent that she has strayed very far from her familiar city existence. She can hear mice scurrying behind the walls and her neighbour Fisher (a very creepy Bernard Hepton) informs her that her home is known as the place of birds in "the old tongue". A mysterious marble appears in her garden, which she somewhat unwisely brings into the house, underscoring the sense that she is being watched. ("Looks just like an eye", says Fisher with gentle menace).

It's a tale "tapping into those age-old stories of what happens to lone females in society, to women who stride out on their own," says Peake, "that unfortunate trope about women who are ostracised, or punished, for being single."

Norah's housekeeper Mrs Vigo (Freda Bamford) insists she attend the harvest festival decked out in a suitably decorated hat. They’re big on harvest celebrations in the village, less so on Christmas. "We don't take much account of that," Mrs Vigo tells Norah. In a striking scene we see the altar piled with autumnal bounty, with corn and freshly slaughtered hares.

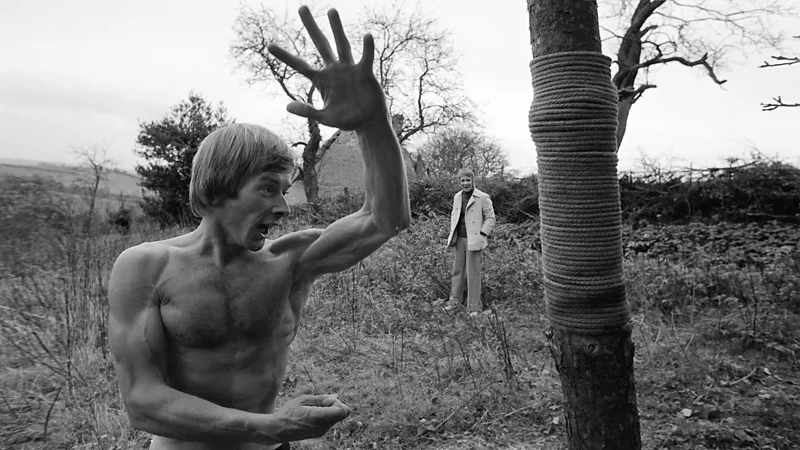

Then Norah meets Robin (Andrew Bradford), as the villagers call him even though his given name is Edgar. She first encounters him in the woods, where he is practicing karate in his underwear. She finds herself attracted to this rather odd, if undisputedly virile young man, despite his habit of babbling about his specialist subject – the SS – when he's nervous. This rather puts a damper on their subsequent dinner date, but events conspire to drive them together. A bird becomes trapped in her house, and Robin is conveniently nearby to come to her rescue.

"Robin's really boring, but she sleeps with him anyway," says Peake. "It's a terrible thing to say, but I think that quite a lot of women could relate to being in that situation, knowing what that kind of sexual exchange is and your currency within it." The film takes Norah's desire seriously. So often women in drama who take pleasure in sex are punished in some way, as Peake notes, pointing out it's still relatively rare to see "women who are taking control of their sex drive and their sexuality this way".

The use of headphones in the stage show will allow the audience to feel like "we're actually in Norah's head," explains Johnson. Her take on Norah will be, she says, "very powerful in the decisions she makes but she will also have a lot of intrusive thoughts [where she] thinks she is just being silly or going slightly mad".

In the film, Norah discovers she is pregnant, her diaphragm having mysteriously gone missing from her bathroom cabinet on the night she slept with Robin, leading to a scene where she matter-of-factly discusses her wish to end the pregnancy with her city friends after leaving the village. She is still determined to have an abortion when Robin comes to plead with her to keep the baby. The film presents the emotional complexity of her predicament, with Norah the rational one and Robin resorting to emotional blackmail.

BFI Rosemary's Baby was released two years before Robin Redbreast – and shared similar themes (Credit: BFI)BFI

Rosemary's Baby was released two years before Robin Redbreast – and shared similar themes (Credit: BFI)

"The 1960s and 70s were a period of rapid social change, where women were entering the paid workforce, struggling for equality, bodily autonomy, and sexual liberation," says Maria J Pérez Cuervo, founder of folk horror small press Hellebore. The 1967 Abortion Act had just come into effect in Britain, which legalised abortion performed by a registered medical practitioner on certain ground, so the issue of abortion was at the forefront of people's minds. "Norah's decision isn't depicted frivolously, she struggles to come to terms with it," she says. "This openness about sexual independence, about a woman's sex life, about abortion and freedom, still feels very fresh today."

The horror comes from seeing the woman's body as an extension of the fertility of the land: her body doesn't belong to her, it is a commodity – Maria Perez Cuervo

Having decided against having an abortion, Norah finds herself heavily pregnant and stuck in the village, her every attempt to leave blocked. Her car breaks down and no one will fix it, the buses won't stop for her, and her phone is cut off. The villagers fob her off with excuses, while conspiring to keep her there until Easter, for what, it becomes increasingly clear, is the completion of some kind of ritual related to her pregnancy and to the earth. She's totally alone and trapped, forced to await her fate.

The film's sources

Both Peake and Johnson are fans of folk horror. Peake has always had an interest in all things other worldly, she says, something which has been apparent in her previous work for theatre. In 2015 she starred in Frankcom's stage production of Caryl Churchill's play The Skriker, about an ancient, shape-shifting fairy. Growing up, she always had a fascination with fairies and "our relationship with Mother Nature", she says. For her part, Johnson's fiction often evokes the eeriness of the English landscape and the fenlands of her childhood. "The back and forth between the earth and us isn't a simple relationship," she says.

Like much folk horror of the era in which it was made, Robin Redbreast draws on Scottish social anthropologist James George Frazer's seminal 1890 work The Golden Bough, an exploration of religion and myth, which features descriptions of human sacrifice and fertility cults. Bowen also spoke in interviews of how he was inspired by the murder of farm labourer Charles Walton in 1945 in Warwickshire, a still unsolved case which came to be known as "the witchcraft murder". (It would also inspire Dennis Pinner's novel Ritual which would in turn provide the inspiration for The Wicker Man). However, Bowen's film also contains distinct echoes of Roman Polanksi's 1968 horror classic, Rosemary's Baby, based on Ira Levin's novel, which also sees a pregnant protagonist isolated and trapped, her body used as a vessel.

In Robin Redbreast, Pérez Cuervo says, "the horror comes from seeing the woman's body as an extension of the fertility of the land: she is Mother Gaia, to be exploited; her body doesn’t belong to her, it is a commodity".

This is also somewhat true of Rosemary's Baby, though that film mixes in tropes of the gothic horror that was popular at time, stories full of women trapped in "a monstrous house or a monstrous family, where the man they had married might – or might not – be a murderer" as Perez Cuervo puts it. Rosemary's husband makes a deal with the Satanists next door in order to further his acting career – Ira Levin, it's worth remembering, was also a playwright, and knew a thing or two about actors – but in Polanski's film, pregnancy is the real source of the horror, "because it is an invasion of her body and her free will, which is something much more horrific and explicit than the usual gothic romance themes". While Norah isn't violated while in a drugged stupor like Rosemary is in Polanski's film, she is essentially used as breeding stock, a repository for Robin's seed.

What gothic and folk horror have in common is a sense of inescapability. There are patterns we are fated to follow. "As women, we're still affected by this," says Pérez Cuervo, "we're aware of the struggles of our mothers and grandmothers and all the women who came before, we're trying to find our place in the world, thinking it might have changed so we might have it easier, but finding similar struggles along the way." It's telling in this respect, that a television film written over half a century ago can still feel so resonant.

-bbc