The blind women detecting early stage breast cancer in India

Only 1% of women in India have ever attended a breast-cancer screening programme. A team of blind and partially sighted women are working to change that, one highly sensitive examination at a time.

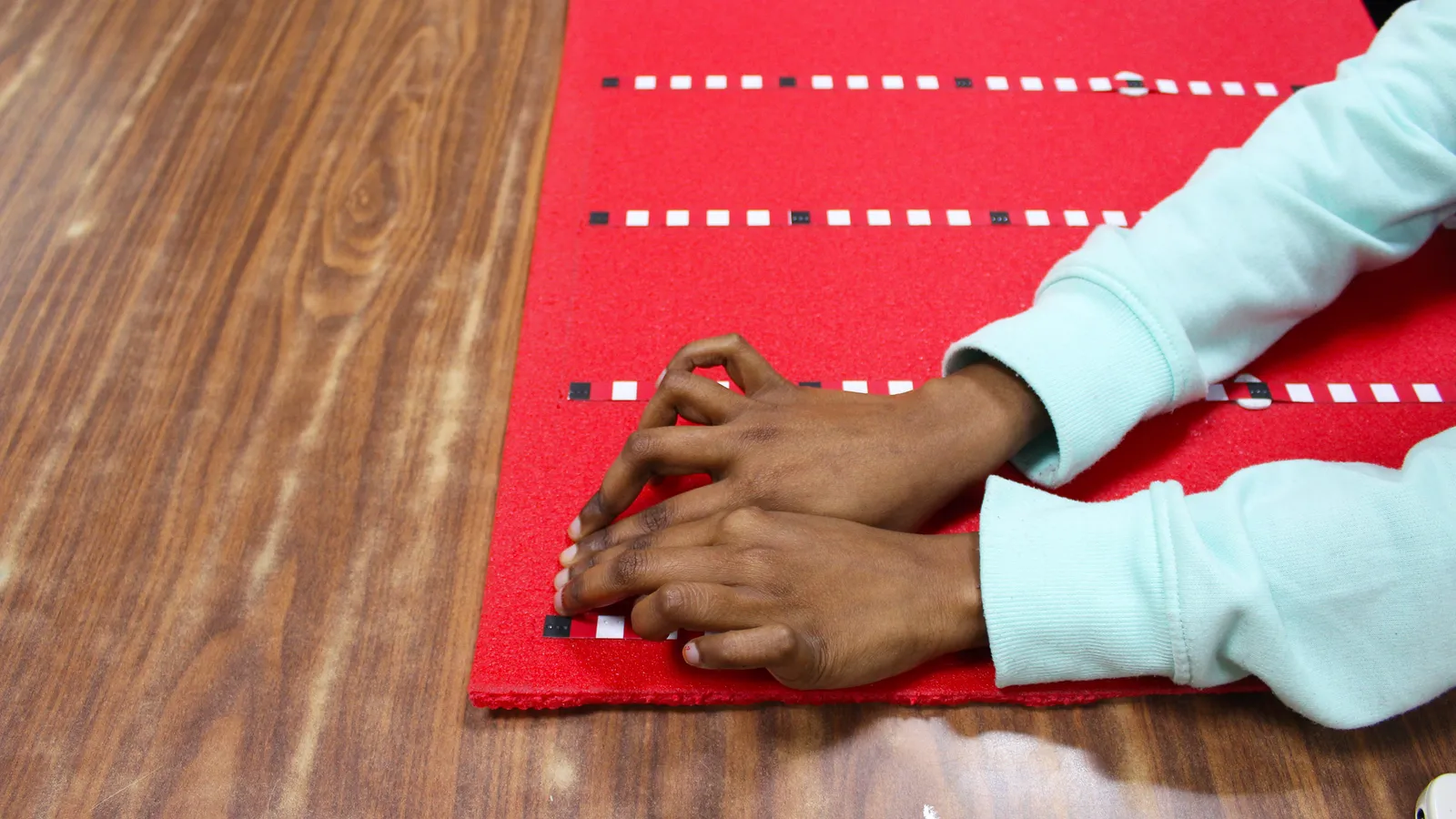

In a bare room in a remote government-run primary health centre in Vapi, a city in the south-west Indian state of Gujarat, Meenakshi Gupta holds a diagram of a woman's breast with five Braille-marked orientation tapes pasted on it. Speaking to the woman sitting on the bed, she says: "I'll paste these skin-friendly tapes on your breast and use my fingertips to check it for any abnormalities."

Gupta asks the woman to remove her upper garments, uses a hand sanitiser, and begins the routine examination. Dividing the chest into four zones with the tapes, she spends 30 to 40 minutes palpating every centimetre of the breast with varying pressure, before documenting her findings on her computer. Along with the patient's medical history, Gupta will later send her findings to a physician for a diagnosis of any abnormalities and advice on further assessment.

Gupta is a Delhi-based medical tactile examiner (MTE), a new and emerging profession for blind and visually impaired women in India and Europe. She is a humanities graduate, blind since birth, trained for nine months in tactile breast examinations, a specialised form of clinical breast examination. Gupta's blindness is not incidental to her role, but something that greatly aids her work.

Studies have proven that in the absence of visual information, the brains of blind people can develop heightened sensitivity in hearing, touch and other senses and cognitive functions. Frank Hoffmann, a Germany-based gynaecologist who developed the idea of MTE has found that during their extensive examinations, MTEs can catch lumps as small as 6-8mm. According to his unpublished research, that is less than the 10-20mm lumps that many physicians without a visual impairment can find during examinations.

In India, 18 MTEs have been trained since 2017. Some of them are currently working at hospitals in Delhi and Bengaluru and a few are employed by the National Association of the Blind India Centre for Blind Women and Disability Studies (NABCBW), a non-profit in Delhi that also provides training.

Overall, less than 1% of women had undergone breast cancer screening between 2019 and 2021 across India

But the practice of training MTEs goes back further, to Hoffmann's own concerns about his ability to detect tumours. "I always worried that as a gynaecologist I didn't have enough time to spend on breast examinations and could be missing out on tiny lumps," he says. Many doctors have little time to carry out 30-40 minute examinations, but a trained non-medical worker with an enhanced tactile sense could be ideally placed to do so, he reasoned.

In 2010 Hoffmann's idea was developed into Discovering Hands, a social enterprise based in Mülheim, in Germany, which trains blind and visually impaired women as MTEs. The first peer-reviewed study investigating the feasibility of the approach showed that MTEs' findings were similar to those of physicians.

Hoffmann saw potential for the method to have a broader impact beyond Germany, as an effective and relatively affordable technique. Breast cancer rates are worrisome across the globe, with female breast cancer the most commonly diagnosed cancer in 2020.

Outside Germany, the country with the greatest number of MTEs is India. Here, breast cancer is the leading cause of death from cancer among women in most states. The majority of cases – 60% – are diagnosed at stage III or IV of the disease, reducing survival rates considerably. One study reported the five-year overall survival rate in Indian women to be 95% for stage I patients, 92% for stage II, 70% for stage III and only 21% for stage IV patients.

In high-income countries, more than 70% of breast cancers are diagnosed in stages I and II. Overall, the five-year survival rate for breast cancers in India is around 52% versus nearly 84% in the US.

Lack of access to medical care, ill-equipped facilities, and fear of out-of-pocket expenditure cause delays in seeking treatment, further reducing chances of recovery.

In 2017, Discovering Hands expanded to India through the NABCBW, whose staff received training from Germany to train MTEs. It's hoped that this new avenue of cancer detection could have several advantages over existing approaches.

The standard test for breast cancer screening is mammography, which involves taking an X-ray of the breast. While this is commonplace in the West, its cost and complexity of use means it is harder to implement in low- and middle-income countries. And since mammography is less effective below the age of 50, alternatives are needed for younger women. One option is ultrasound – however, due to the high costs of employing radiologists and the ultrasound machines themselves, "they are not an affordable option for every medical facility", says Mandeep Malhotra, a surgical oncologist practising in Delhi and Gurugram.

A recent 20-year-long Indian study concluded that a clinical breast examination carried out every two years by primary health workers could help catch breast cancer at its early stages. This could reduce mortality by the disease by nearly 30%, in women over 50, the study concluded, however no significant mortality reduction was seen in women under 50. Breast examination is also a more affordable method, making it easier to implement in low and middle-income countries.

Clinical breast examination screening programmes exist in India, but participation rates are "extremely inadequate", according to a recent National Family Health Survey, which provides national data on population dynamics and health indicators. Overall, less than 1% of women had undergone breast cancer screening between 2019 and 2021 across India.

That is why training a para-health force of non-medical blind women to conduct specialised examinations could help in a big way, says Kanchan Kaur, senior director of breast surgery at Medanta super-speciality hospital, Gurugram. "It would mean finding smaller lumps in early and more curable stages of the disease by reaching out to a population that resists seeing a doctor because they feel healthy," she says.

Examinations by MTEs are not meant to replace doctors or mammograms, but rather to take place work alongside medically trained teams as a first step for accurate routine breast cancer screening examinations, available even in areas with limited access to electricity.

Kaur explains that by positioning the MTEs in breast cancer screening camps and the government's primary health centres (which are the first point of medical contact for a large population), women would become familiar with breast examination and get into a habit of self-examining. It would increase overall breast cancer awareness and literacy, and raise the chances of early detection. "When free examinations are available at close proximity, women will get it done," Kaur says.

Currently, Indian MTEs work with surgical oncologists where they examine women coming for routine examinations. Some have been travelling with breast cancer screening camps conducted by NABCBW in rural, semi-urban and urban areas in Mumbai, Delhi, Vapi, and Bengaluru. To date, 14 MTEs have examined a total of more than 2,500 women in camps and approximately 3,000 in hospitals. They also participate in breast cancer awareness campaigns conducted in businesses, schools and universities, where they also offer examinations.

A new wave of research on the work of India's MTEs is promising. Malhotra conducted a study on 1,338 women examined by the MTEs before the pandemic, comparing MTEs' findings with radiological results of the same women. Malhotra found that the MTEs had a high sensitivity for detecting malignant cancers, at 78% (sensitivity is the measure of "true positives"). The number of malignant cancers that the MTEs missed ("false negatives") was very low, at 1%.

Malhotra says that a low miss-rate is critical in cancer screening. "When an MTE finds no abnormalities, we can be assured that the woman has a healthy breast at the moment and needs no further examination," he says. An Austrian study which compared physicians and MTEs found that the latter had a higher specificity and sensitivity. They were especially effective compared with physicians when examining patients with denser breast tissue, which typically makes detecting lumps harder.

Accuracy is not the only thing that an MTE brings to the table. She collects important data about lifestyle habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption, lactation, menstruation and family history of cancers before examining a woman, which gives vital information to a doctor about her potential risk to the disease. As part of her practice, she brings the attention of the woman to all that she checks, such as nipple discharge and asymmetry between the breasts. Towards the end of the examination, the MTE teaches the patient the right way to do a breast self-examination.

Perhaps most importantly, MTEs help reduce the discomfort that women experience from undressing for a breast examination by a clinician who has no visual impairment. This could potentially increase participation in screenings. Sulekha Paswan, a homemaker who got her breast examination done by Gupta at Vapi, said she found the procedure with Gupta more comfortable. And with the time and effort Gupta put into the examination, Paswan thought she was quite thorough.

So far, Hoffmann has taken the Discovering Hands training to India, Austria, Colombia, Mexico, Nepal, and Switzerland. During the pandemic, when MTEs could not work, many took on other jobs. In South America and Nepal, the programme is now on pause. Germany, where the programme has run since 2010 has four trainees and 53 practising MTEs in 130 hospitals and clinics, and a dedicated Discovering Hands centre in Berlin. Austria had trained MTEs in 2015 but for the first few years they were involved only in a study. Since 2021, three MTEs are working in six gynaecological and radiological practices in Vienna, with another three in training. Switzerland is also training three MTEs.

In India, a total of 18 MTEs have been trained, though the pressures of the Covid-19 pandemic have meant only six are currently practicing. Another eight MTEs, however, are in training in Delhi and Bengaluru and are due to graduate this year.

Shalini Khanna, the director of NABCBW explains that the number of trainees is small due to the high expense of the training and because most blind women in the programme come from low-income backgrounds, and may have a pressing need to provide for themselves and their families. The length and rigorousness of the training sometimes means they sometimes prefer to join shorter courses or quit the training midway.

Khanna says that some medical facilities have shown resistance to hiring MTEs because so far Indian research on the impact of MTEs is in its early stages, and some have shown hesitance on financial and logistical grounds. However, many facilities do not see these as barriers, and are choosing to pursue the services of MTEs.

Rajendra Badwe, the director of Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, one of the largest cancer hospitals in India, says that in order to be scaled, the MTE model requires more publicity among the medical community, and acknowledgement and support from the government.

The Tata Memorial Hospital is working on a two-pronged approach to scale up the MTE model in India. "We are planning to connect with organisations and individuals that have access to blind women for training them, and to talk to the government about integrating the MTEs in the public breast cancer screening program," Badwe says.

Gupta thinks that the expansion of the MTE model could help more blind girls find a dignified job, as well as dispelling myths about the condition. "Maybe then someday people will stop asking us how you commute, how you use your laptop, and understand that we don't always go to the hospital for treatment. We can go there to work," she says.

-bbc