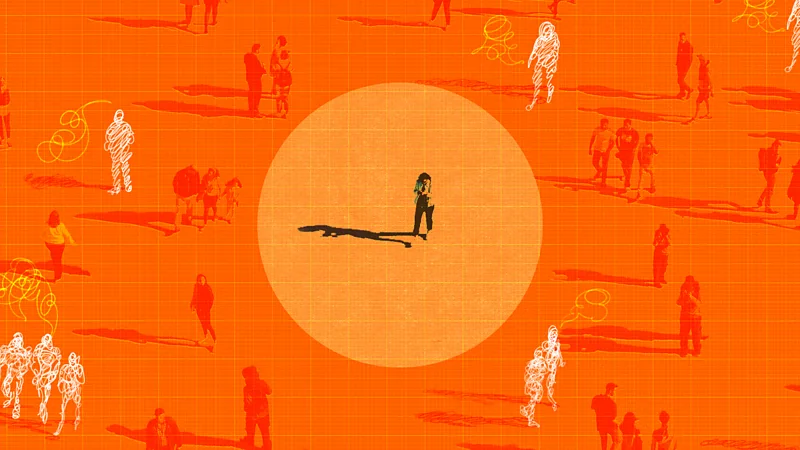

Why do I feel so lonely even though I'm surrounded by people?

We live in a bustling, crowded world, yet loneliness appears to be on the rise. Why are so many of us feeling isolated and what can we do about it?

There are many kinds of loneliness – everyone feels it differently. But what is it to you?

Perhaps loneliness is a city. On its streets, among the hubbub, the crowds, the chatter and laughter, you remain a stranger – discombobulated, disconnected, in the way.

Maybe it's a relationship turned sour. A marriage or partnership of unheard words and unmet needs. You're there, but never seen.

Or perhaps you feel like Robert Walton, the polar explorer from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, who is surrounded by dependable shipmates but really just craves one true friend, "the company of a man who could sympathise with me, whose eyes would reply to mine".

It's common knowledge that physical isolation can lead to loneliness – and few things are as painful as the chronic, imposed solitude experienced by many of society's most vulnerable.

But if you've ever experienced situations like those described in the opening sentences of this article, you might also have suspected that other people – counterintuitively – aren't always the antidote to loneliness. They may even be part of the problem. In fact, we can just as easily be lonely in a crowd, in a romantic relationship, among friends.

It is an experience that was recently confirmed by a 2021 study involving 756 people who regularly recorded how they felt using a smartphone app over a two-year period. Feelings of loneliness seemed to increase in overcrowded, densely populated environments – in other words, modern cities. Could it be that our increasingly urban, technology-dominated lifestyles are making us feel less connected to one another? And are there solutions hiding within these findings?

It's certainly important to understand this paradox. We're reportedly living through a "loneliness epidemic" – a global outbreak that knows no boundaries, affects young and old, and can even rewire our brains. The BBC Loneliness Experiment, which sampled 55,000 people around the world in 2018, found that 40% of 16 to 24 year olds feel lonely often or very often. Other studies show that around 10% of adults around the world feel lonely – and in many different ways.

But it comes at a time when we have arguably never had more ways of connecting with others thanks to technology that lets us dial up friends and family on the other side of the globe, chat online with people we have never met, and follow the lives of those we know in social media feeds. Urban populations are also growing rapidly, with 68% of the world's people expected to be living in cities by the middle of this century.

So, in our busy, technology-connected world, why do we still feel lonely, even around others? And is it really another pandemic – something always to be avoided, medicalised, eradicated, stigmatised? Or can we also learn from it

Loneliness is a fuzzy, complex concept, something we all experience in our own way. Fay Bound Alberti, professor of history at King's College London and author of A Biography of Loneliness, argues that loneliness, rather than being a single state of mind, is actually a "cluster" of emotions, which may include feelings such as grief, anger and jealousy. Her research reveals it is also a relatively recent "invention", with the word only taking on its current meaning around the year 1800 (more on this later).

Nevertheless, loneliness is now generally defined in science as the disconnect between actual and desired social relationships – reflecting the reality that you don't have to be alone to be lonely.

Sam Carr, a psychologist at the University of Bath who researches human relationships, believes the "biggest myth" is that people are always the solution to loneliness.

"People can actually be the cause of it," says Carr, who is also the author of All the Lonely People, an exploration of people's diverse experiences of loneliness. "Everyone's a sort of jigsaw piece and we want to feel like we fit in. And other people often can be the reason we don't feel like we do. Even if they're a friend or partner, perhaps they don't recognise us for who we are. Or they make us feel invisible. Or we have to pretend we're someone else in their company. For a lot of people, this seems to be the essence of their loneliness."

Bound Alberti agrees that physical isolation from others is not necessarily what makes people lonely.

"People think that being lonely means you have to be alone," she says. "But my research shows it's not so much the physical distance from others that makes us feel most lonely, but the emotional distance. The loneliest people are those in relationships that should be fulfilling – but are not. Some of the loneliest times I've experienced have been when I've been surrounded by too many people that I'm not remotely on the same wavelength as."

Carr recently received a letter from America. Its author revealed that she's been married to her husband for half a century. She also revealed that he's always been the source of her loneliness. She'd hoped marriage would be the cure – it ended up the cause.

After all, if one partner prioritises physical connection while the other craves an inquiring, intellectual bond, they may well end up lonely, together.

"It can be about perception – whether you feel like your needs are met," says Olivia Remes, a mental health researcher at the University of Cambridge and author of The Instant Mood Fix. "Some people with a strong connection to just one person don't feel lonely, while others, who are surrounded by many people, but want deeper connections, do."

Feeling lonely is hardwired into our humanity. Some believe it serves an adaptive, evolutionary function that encourages us to take action to promote our short-term survival. Just as hunger tells us to find food, so loneliness, says Remes, "tells us something is wrong with our social environment and that we need to do something about it".

For our prehistoric ancestors, isolation was dangerous. It made them more vulnerable to animals and other hazards – and therefore less likely to survive and pass on their genes. So a sense of loneliness, however it was experienced back then, may have been a neurological mechanism for encouraging them into the safety of the group.

But times change. And so do attitudes to loneliness and solitude. Bound Alberti's research argues that prior to the 19th Century, the language of "loneliness", as we use it today, didn't really exist. Back then, to be "lonely" simply meant to be singular, "one-ly". It was rarely something bad. Being alone enhanced connection to nature or God by stripping out the background noise.

"It was a language of 'oneliness'," says Bound Alberti. "And I love this term – I wish it would come back into fashion. When [the poet] William Wordsworth wrote about wandering 'lonely as a cloud', he was simply talking about being alone. It didn't mean he had the emotional lack we now associate with the word [lonely]."

But societies around the world changed radically over the next two centuries. Bound Alberti argues that as religious and other traditional belief systems weakened, cities grew, communities and families dispersed, so people became more "anonymous" and less connected. The rise of individualism, which has been in some studies, may also have played its part.

"When I look around and see the lack of social care, the lack of connectedness, the lack of an ability to feel like we belong except when we're buying things, which is increasingly the only way we come together in physical spaces, it seems to me that it's not really any surprise that we feel lonely," says Bound Alberti. "The weird thing would be if we didn't."

So, what can we do if we feel lonely, despite being surrounded by people? First, distinguish between passing and chronic loneliness. "If you feel like the symptoms that you are experiencing are stopping you from living your life, from working, from building relationships, if they're distressing, it's worth going to a medical professional and sharing what you're going through," says Remes.

It's also important to distinguish between loneliness that is imposed and that which is chosen, says Bound Alberti. After all, we can all choose to isolate ourselves, but many people face structural circumstances – from age and health issues to poverty and discrimination – that impose isolation upon them. These structural factors need urgent redress at a community and government level, she says.

But a common problem at the personal level is that we're often reluctant to connect with people, particularly strangers – despite the proven benefits. In a 2014 study, researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of California Berkeley investigated why.

They began by asking Chicago commuters whether chatting with a stranger would improve their morning journey. Most thought not. But when the researchers split the sample into groups, randomly tasking some with doing just that and others with staying schtum, those who did make conversation enjoyed their commute the most.

The experiment also challenged another of the participants' innate pessimistic biases. Beforehand, just 40% of those travelling by train thought they'd find a willing chatterbox to natter with. In fact, they all did. The findings even prompted some UK rail providers to introduce temporary "chat carriages" in 2019 in an experiment with the BBC, while a bus company placed "conversation starter" cards on its routes.

Indeed, believing we're less likeable than we are is a widespread human trait dubbed the "liking gap". And it really might be holding us back, particularly if we're already lonely.

"The lonelier we get and the more habituated we are to loneliness, the harder it is to reach out," says Bound Alberti. "So, if you're used to being alone and used to feeling rejected, you presume that someone's facial expression is rejecting you or their body language is rejecting you. And that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy."

No-one is advocating hassling someone who'd rather be left alone, but next time you're feeling lonely in a crowd, try – respectfully – striking up a conversation with someone standing nearby. Or even set yourself challenges to talk to someone new each day – research suggests the more you do it, the more your confidence will grow and your fear of rejection will diminish. Even short conversations to say hello or thank you can go some way to make you feel better. (Find out more about the benefits of talking to strangers in this article by Joe Keohane.)

But we should also recognise that beating loneliness isn't just about forming connections. We need to build and nurture meaningful connections.

Remes suggests that volunteering is a powerful way of doing this. "Helping others takes the spotlight off ourselves and what we're going through," she says. "Instead, we're placing our attention onto another individual and thinking about how we can make a difference to them. It helps us to feel connected, which lowers levels of loneliness."

Touch is also important. The amount of physical contact people desire varies greatly between individuals. But there is a link between loneliness and a lack of touch – and even a quick touch on the shoulder can lead to enhanced feelings of social connection. Indeed, a 2020 study found that participants who received brief physical contact felt significantly less neglected, especially if they were single.

But being with people isn't the only way to feel connected. Time with pets can also create a sense of belonging as can getting out and enjoying nature.

Indeed, the 2021 study – that found people who lived in overcrowded urban areas were more likely to feel lonely – also found that the sense of loneliness decreased with perceived social inclusivity and contact with nature. In fact, those who were exposed to nature were 28% less likely to experience loneliness.

"The reason that contact with nature is helpful is that it increases our attachment to a place. It makes us feel like we belong," says Remes. Indeed, it seems that this sense of connection, belonging and inclusion is the real antidote to loneliness. (Read more about how spending time in nature can make you feel less lonely in this article by Julia Hotz.)

We should remember that some relationships can also leave us feeling lonely. Whether it's with a friend or romantic partner, we can experience loneliness in a relationship when we feel unseen, unheard or like we have to wear a mask or be someone we're not in another person's company. If this is you, allow time for communication. Tell your friend or partner what you need and give them the space to share their priorities in return. Perhaps the relationship is toxic, in which case you should consider leaving it. But you may also have built walls or developed diverging interests and needs over time, obstacles that can be overcome.

Whenever we experience feelings of loneliness, it's always worth asking what those feelings are trying to tell us. But Remes also suggests that we should be wary of the answers we give ourselves. When we're lonely, we may well ask, 'why?'. But our answers can have significant consequences. If we answer the question, "Maybe I’m lonely because I haven't reached out to people as much as I should have", for example, then that can be motivating. The answer contains a manageable solution – I need to reach out more – which can spur you into action.

But if you answer the question, "I am lonely because I'm unlikable" or "I'm unlucky", then the solution – I need to be more likeable or lucky – will feel abstract and further from your reach. "The key is to see the situation as being within, rather than beyond, your control," says Remes.

And despite talk of loneliness being an "epidemic", and the stigma that's often attached to it, remember it's not always bad. Whether we feel isolated in a crowd, a relationship or at the ends of the Earth, loneliness is part of who we are.

"If you go through a whole human life, the things you feel connected to often end," says Carr. "That might be a marriage, or a job or a bereavement. Most of those things eventually end for one reason or another – they're kind of transient. And what most humans have to do is reinvent themselves after that and reconnect with something else. But that doesn't happen overnight.

"There's a period, a sort of a desert, you've got to cross to become a new you. And it's inevitable that it's going to be quite lonely crossing that desert. But we should appreciate that as a part of the existential reality of being human rather than some indication that we're broken or need fixing."

As the world gets ever busier, finding better ways of connecting with others may be something we could all benefit from. But we also shouldn't be too critical of ourselves when we do feel lonely. Don't forget it's a natural, diverse and sometimes helpful phenomenon that we should listen to, not simply stigmatise.

-BBC