Why Nigeria’s ‘Mr Flag Man’ has waited a year to be buried

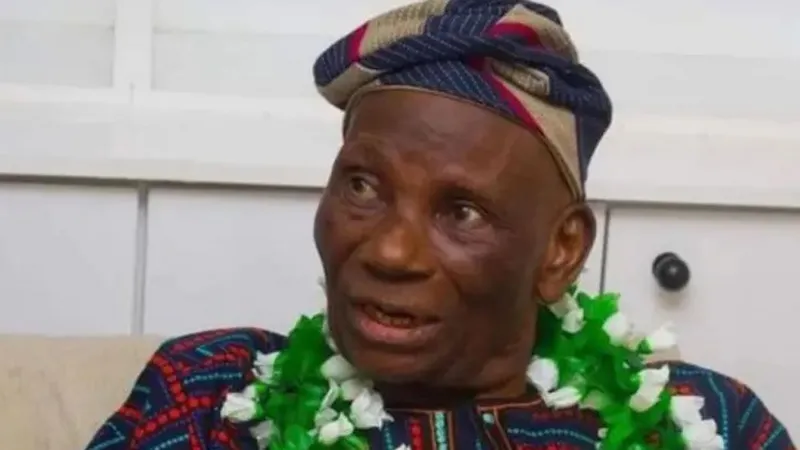

The family of the man who designed Nigeria’s national flag have told the BBC they have given up waiting for a promised state funeral, a year after he died.

Instead Taiwo Michael Akinkunmi, who died a year ago aged 87, is going to be buried this week in Oyo state, where he lived.

Akinkunmi, known by many as “Mr Flag Man” and whose house was painted in the distinctive green and white colours of the national flag, was a humble man.

But his son hopes that during his send-off, which Oyo state has agreed to fund, he will be remembered for the design that became a symbol of a united Nigeria.

“We have to give him the befitting burial he deserves,” his son Akinwumi Akinkunmi told the BBC Focus on Africa podcast.

Taiwo Akinkunmi always said he was an unlikely flag designer. He entered a competition for a new design ahead of Nigeria’s independence from the UK in October 1960.

At the time he was studying electrical engineering in London and had spotted a newspaper advert about the competition.

According to flag expert Whitney Smith, 3,000 designs were submitted - “many of great complexity”.

But Akinkunmi’s was a simple affair, with equal green-white-green vertical stripes - and it replaced the colonial flag that had included the British union jack and a six-pointed green star under a red disk.

AFP Nigeria's Blessing Ejiofor (L) and Pallas Kunaiyi-Akpanah (R) celebrate with their country's national flag after a Nigerian basketball victory at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games - 4 August 2024AFP

Akinkunmi’s original design included at its centre a red sun surrounded by rays. This was intended as “as a symbol of divine protection and guidance”, Mr Smith wrote in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

However the sun was omitted by the committee, which awarded the then 23-year-old £100 (then worth $280) for his winning design.

Akinkunmi always said his inspiration came from his childhood as he had travelled and lived in various parts of Nigeria.

Born in Ibadan in the south-west, now capital of Oyo state, he spent his early years in the north of the country because of his parents’ work. He grew up in what he said was a happy polygamous family and was one of his father’s 10 children.

He returned to Ibadan to finish his education. He once told ThisDay journalist Funke Olade that his secondary school was like a “mini-Nigeria” as it had students from all over the country.

Nigeria is home to more than 300 ethnic groups and while Africa’s most populous country has no official religion, the nation is roughly divided between the mainly Muslim north and the largely Christian south, though many communities are mixed.

For Akinkunmi the green in his flag symbolised the nation’s rich agricultural heritage, while the white represented peace and unity.

“It is typical that Nigeria, like many other culturally diverse countries, chose a simple flag design. A more complex design might have explicitly honoured some ethnic and religious groups while excluding others,” Mr Smith wrote.

Agriculture was always close to Akinkunmi’s heart and he was excited to return to Nigeria after independence to take up at a job with the Ministry of Agriculture, where he worked as a civil servant until he retired in 1994.

But for much of his life very few people knew about his contribution to the country, though wherever he lived he reportedly used to paint the outside of his house green and white.

It was not until Nigeria celebrated its 50th year of independence that he was recognised as one of 50 distinguished Nigerians.

His son says an Oyo state politician later lobbied for him to be given a national honour and pension - and in 2014 he was made an Officer of the Order of the Federal Republic (OFR), one of Nigeria’s highest awards.

After Akinkunmi’s death last year, a senator sponsored a successful motion that he be given a state burial.

However, no plans have ever been made and as they waited, Akinkunmi’s family have been paying 2,000 naira ($1.30; £1.00) a day to keep the body at a morgue.

The flag designer’s son said that in June they found out that the arts ministry’s National Institute for Cultural Orientation (Nico) had been directed to sort out the state funeral.

But apart from one phone call, he said the institution had failed to communicate any further.

He feels waiting any longer would just sully his father’s name.

This is when the Oyo state government decided to step in to fund the burial rites for the flag designer.

“My late father was an easy-going person who didn’t want anything to tarnish his image,” his son told the BBC.

“He was well brought up, he was a very intelligent man, and a good person that everyone wanted to associate with,” he added.\

-BBC