An AI started 'tasting' colours and shapes. That is more human than you might think

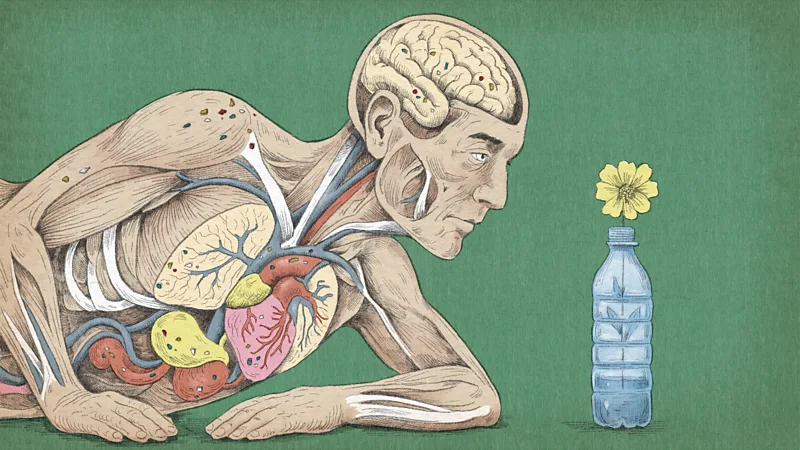

The brain often blurs the senses – a fact that marketers often use in the design of food packaging. And AIs appear to do the same.

What is the flavour of a pink sphere? And what is the sound of a Sauvignon Blanc?

Such questions may sound ridiculous, but a huge body of literature shows us that the human brain naturally merges sensory experiences. We may not be conscious of the phenomenon, but we associate different colours, shapes and sounds with different flavours in ways that can subtly shape our perceptual experience, for example.

The colour of our glass, or music playing in the background of a bar, can determine how sweet or musky a wine tastes, for instance. "This cross talk between the senses is happening almost on an ongoing basis all the time," explains Carlos Velasco at the University of Oslo in Norway. In extreme cases it can manifest in a blurred sensory experience for some people where words might trigger specific tastes or music produces a riot of colour – something known as synaesthesia.

And while the idea that you can "taste" a colour or sound may seem absurd enough, Velasco's latest research suggests that generative artificial intelligence systems may also do this too. As with all AI algorithms, this is largely a reflection of biases in the data they were trained on, so they are perhaps just highlighting how common these associations may actually be. But Velasco and his colleagues hope to use this fact to find many other ways to hack human senses.

Eating with the eyes

First, a note on terminology. Scientists use the term "sensory modality" to describe the means that the body uses to encode information – through, for example, our taste buds, ear drums, the retina in our eyes or the "tactile corpuscles" in our skin. The associations that we tend to form between different sensory qualities are therefore known as "cross-modal correspondences".

Experimental evidence for this phenomenon first emerged in the 1970s, with studies suggesting that red and pink hues are associated with sweetness, yellow or green with sourness, white with saltiness and brown or black with bitterness. These general patterns have now been replicated many times since, using multiple experimental methods.

Participants may be asked for their subjective judgement of abstract questions such as: "On a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most sweet, how sweet is the colour red?" From this, you can see that, on average, each colour has a unique flavour profile shared by large numbers of people across different cultures. A multinational collaboration, led by Xiaoang Wang at Tsinghua University in China, found similar cross-modal correspondences in Chinese, Indian, and Malaysian participants.

Alternatively, participants may be given a particular food or drink presented in multiple colours, and asked to judge the taste of each one. Eriko Sugimori and Yayoi Kawasaki at Waseda University in Japan, for instance, have found that bitter chocolate tastes considerably sweeter when it is wrapped in pink, rather than black, packaging.

The shapes of food can have similar effects. We tend to associate rounder shapes with sweetness, while spikier shapes are considered to be more sour or bitter – with knock-on effects on people's perceptions of the foods. We eat with our eyes as well as our tongues.

The origin of these associations is still a matter of debate. "The safest assumption is that we learn them all," says Charles Spence, the head of the cross-modal research laboratory at the University of Oxford. "They could be thought of as kind of the internalisation of the statistics of the environment. In nature, fruits go from green, when they are sour, to redder and warmer hues, when they are sweeter. If we internalise that statistic, associating reddish hues with sweeter taste, we know which trees to climb for the for the fruit that will sustain us."

The associations between shape and taste are harder to explain. "It may be the emotions associated with or triggered by the stimuli," Spence says. We may associate sweetness with pleasure, for example, and we prefer round shapes since they are less likely to hurt us, compared to something sharp. As a result, we start to associate sweetness with curviness through this indirect association. Bitter substances, in contrast, are more likely to be poisonous – and so we might link them to sharp shapes that also have more potential to cause bodily harm.

Associative AI

The rapid rise of AI inspired Velasco, Spence, and their colleague Kosuke Motoki at the University of Tokyo to investigate whether generative AIs – trained on human data – would report the same associations. They asked the AI-powered chatbot ChatGPT to answer the same kinds of prompts that had previously been given to human participants. For example:

"To what extent do you associate round shapes with sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami tastes? Please answer this question on a 7-point from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much)."

And…

"Among the 11 colours listed (black, blue, brown, green, grey, orange, pink, purple, red, white, yellow), which colour do you think best goes well with sweet tastes?"

Averaging their results across hundreds of chats in English, Spanish and Japanese, the researchers found that the AI did indeed reflect the patterns commonly found in human participants – though there were some differences between the versions of the AI they used.

Overall, ChatGPT-4o more reliably reflected the human associations than ChatGPT-3.5. "The differences likely stem from variations in model architecture, such as the increased number of parameters in ChatGPT-4o, as well as a larger and more diverse training set," says Motoki.

Of all our festive favourites, then, what tunes would go best with mulled wine and mince pies?

Silicon brainstorming

Intrigued, I decided to investigate whether other large language models (LLMs) such as Google's Gemini, might also reflect our sensory associations. When I asked it to say what colour is sweetest, it responded: "Many people associate pink with sweetness, likely due to its association with sugary treats like cotton candy and bubble gum." It also named green for sour, white for salty, and black for bitter.

The match would seem almost uncanny – except, midway through its answer, Gemini pointed me towards one of Spence's previous research papers on these cross-modal associations, suggesting that it had drawn its response straight from the scientific literature.

Spence had mentioned this possibility in our conversation. "Given that we tested the large language models on what is already known, and what is already hence published in literature, maybe it's just feeding back what it has read," he says.

In the future, he hopes to investigate whether generative AIs can generate hypotheses for other cross-modal correspondences that have not yet been documented in the scientific literature, but which could then be tested on human subjects.

"You could potentially use large language models and generative AI to discover the perfect correspondences to whichever dimensions you're interested in," he says. This approach might then be useful for marketeers who hope to design products or packaging that riff on our brain's existing associations.

There are some caveats, of course. AIs can sometimes "hallucinate" – that is, make up misleading responses to questions. And even if their responses are reliable, they may lack the nuances or idiosyncrasies provided by our own brains that can add excitement or interest to designs. Sometimes, you may wish to riff on the intuitive associations between sensory qualities without necessarily copying them entirely.

For this reason, any cross-modal correspondences identified by AI will need to be combined with human creativity, says Velasco. "It's inspiration, rather than a definite solution."

Christmas accompaniments

We will need more evidence before we place too much faith in AI's judgements, but writing this piece in the run-up to Christmas, I couldn't help but wonder whether ChatGPT could give me some advice for a drinks party.

Spence has previously shown that people tend to agree on which pieces of music complement different types of wine. With its high tempo and pitch, Debussy's Jardin Sous la Pluie seems to go better with citrusy whites, while the piano and cello duet of Rachmaninoff's Vocalise tends to bring out the fuller-bodied flavours of reds.

Of all our festive favourites, then, what tunes would go best with mulled wine and mince pies?

"The complex flavour profile of mulled wine – rich with spices like cinnamon, clove, and star anise, combined with fruity and warming notes – calls for music that is equally layered, warm, and evocative," ChatGPT told me. "A perfect accompaniment could be Carol of the Bells performed with a lush orchestration. Its cascading, layered melodies evoke a sense of festive magic and warmth that mirrors the interplay of spices in mulled wine."

I'm not sure that's quite the vibe I'm going for – you might recall that piece of music's use in a key tension building scene in the Christmas film Home Alone – so I ask for some pop or jazz alternatives.

"Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas performed by Ella Fitzgerald or Diana Krall. The sultry, smooth tones of jazz vocals and warm instrumentation echo the comforting and layered flavours of the mulled wine," it suggests. Other options include Underneath the Tree by Kelly Clarkson "emphasising the celebratory spirit while balancing the wine's depth with an energetic vibe" or Christmas Time is Here by the Vince Guaraldi Trio, "a mellow yet jazzy track with just the right amount of sophistication and charm to enhance a relaxed festive evening". We'll see if my guests agree.

-BBC