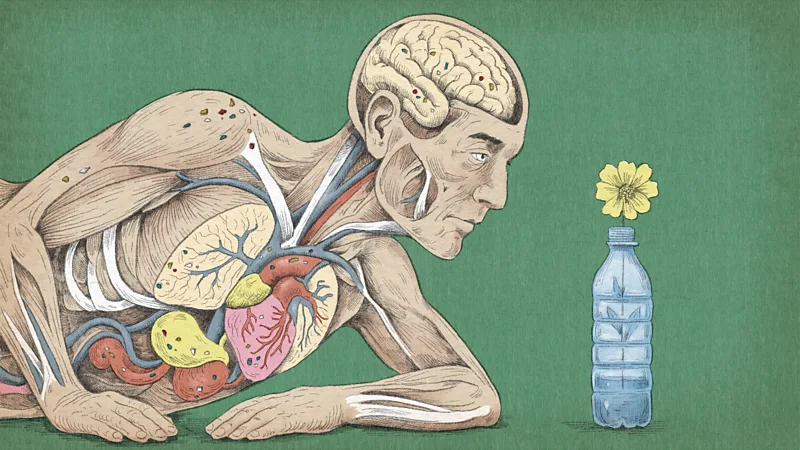

How do the microplastics in our bodies affect our health?

Microplastics have even been found inside our bones – but what impact are they having on our health? Here's everything we know about what they're doing to our bodies.

A field in a sleepy corner of Hertfordshire, barely an hour's drive north of London, houses the world's longest running agricultural experiments.

Initiated by Victorian aristocrat and landowner John Bennett Lawes, who later became a successful pioneer of modern fertilisers, the aim was to test out various ideas for boosting wheat production. But without the help of modern technology, the only means of storing data was to meticulously collect samples of dried wheat grain, straw and soil from the field and bottle them away.

When it started in 1843, Lawes had little idea that this tradition would endure for another 182 years, creating a remarkable archive of samples. Now housed at the research facility Rothamsted Research, in Harpenden, the collection reflects many of the changes that human activity has inflicted on the planet in the past two centuries.

Andy Macdonald, the current custodian of the archive at Rothamsted Research, affectionately known by colleagues as "Keeper of the Bottles", says that samples collected during the 1940s and '50s contain radioactive traces – reflecting the fallout from the era's nuclear weapons testing. But there's another unwelcome record which can be found in these bottles of ancient soil – the first emergence of microplastics.

According to one famous estimate, we might consume up to 52,000 microplastics per year, and while that precise figure has been subsequently challenged, it's clear that they are entering the human body in significant quantities. Whether ingested through our food, the liquids we drink, or absorbed from the air we breathe, microplastics have become ubiquitous. They have been found in bodily fluids from saliva and blood to sputum and breast milk, along with an array of organs including the liver, kidneys, spleen, brain and even the insides of our bones. This steady convergence of evidence has all pointed to one question – what exactly is all this plastic doing to our health?

In the samples housed at Rothamsted Research, Macdonald says that there's a clear dividing line before and after the plastic era began. "The use of plastics in society first came into being on a large scale in about the 1920s, and we see a big increase from the 1960s onwards," he says. "Some would have inevitably ended up in the soil through atmospheric deposition, and you can also imagine microplastics being shed from tractor tyres."

Today it's thought that around the world, humans are ingesting and inhaling more microplastics than at any time in recorded history. In a study published in 2024, scientists found that consumption of the particles has increased sixfold since 1990, particularly in various global hotspots including the US, China, parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Scandinavia.

But finding out how they are affecting our health has proved tricky. One way to find out is what's known within medical circles as a "human challenge trial". Usually carried out in the realm of infectious diseases, it involves participants agreeing to be deliberately infected with a pathogen in order to help scientists better understand its effects on the human body.

And so, in early 2025, eight brave volunteers entered a lab in central London, and willingly gulped down a solution of microplastics in return for a small fee. This particular study, funded by the Minderoo Foundation, represented the first time that such a challenge trial had been carried out with plastic – though the results haven't been published yet.

The concept, according to Stephanie Wright, a researcher at Imperial College London who led the trial, is that many of us are unwittingly carrying out this exact experiment on our own bodies on a daily basis. The team copied some of the common ways through which many of us ingest microplastics, for example dipping plastic sealed tea bags in hot water or microwaving fluids in a plastic container, before asking the volunteers to drink the liquids and then attempting to follow what happens next.

"We know that heating and hot water are the worst-case scenarios for plastic ingestion, and that can really facilitate the release of microplastics from commonly used plastic items," says Wright. "So we want to take some of these scenarios and try to see how many of these microplastics are actually absorbed across our gut and back into the blood."

To assess this, Wright measured the volunteers' blood at repeated time points over the course of 10 hours. The data, when published later this year, will provide the first concrete information on the typical concentrations of microplastics which end up circulating around our bodies in the wake of a cup of tea or a microwaved ready meal, and their size.

In the eyes of Wright, such information will represent another step on the path to better understanding the potential health risks for the average person. She predicts that the kinds of microplastics which reach the bloodstream are the smaller particles, but despite a range of investigations in animals and test tubes, we have almost no data on how a dose of microplastics might impact a typical healthy individual.

"We need to know how much gets back in, compared to what was originally ingested," says Wright. "And then the greater concern is where they are ending up, and are they accumulating somewhere? It's very unlikely that our body is capable of completely breaking them down. And can that lead to things like chronic inflammation and tissue scarring which compromises the function of organs?"

These questions are arguably especially pertinent, as in the last year, various studies have emerged which sent shockwaves through the medical community.

In late 2024, Chinese researchers discovered microplastics within samples of bone and skeletal muscle from a group of patients who had undergone joint replacement surgery, either on their elbows, hip or shoulders. In the study, the scientists expressed concern at this finding, speculating that the presence of microplastics within bone or muscle could impact an individual's ability to exercise, with other studies showing that certain types of microplastics can impede the growth of bone or muscle cells.

This followed another paper in early 2024, where a group of Italian researchers identified microplastics in plaques found in the carotid arteries – a pair of major vessels which deliver blood to the brain – of people with early-stage cardiovascular disease. This linked their presence to worsening disease progression. Over the following three years, individuals carrying these microplastics in their plaques had a 4.5-fold greater risk of stroke, heart attack or sudden death.

Then in February 2025, another group of scientists identified microplastics in the brains of human cadavers. Most notably, those who had been diagnosed with dementia prior to their death had up to 10 times as much plastic in their brains compared to those without the condition. "We were shocked," says Matthew Campen, a University of New Mexico toxicology professor who led this study.

When it comes to the brain, Campen's current belief is that tiny plastic particles circulating in the bloodstream might be hijacking the brain's high metabolism and hitching a ride into our central nervous system on the back of the fats known as lipids which it requires for energy.

"We also think that the high lipid content of the brain, especially in white matter, makes for an ideal environment for these plastics," says Campen. "The brain also has a notoriously slow clearance mechanism, and in dementia, the blood brain barrier [which is designed to stop foreign objects accessing the brain] is impaired, further aiding uptake of plastics."

But both Campen and the Italian researchers who found microplastics in the carotid arteries have stopped short of claiming a direct causative link between microplastics and either dementia or heart disease. Rather than acting as a single driving factor for these illnesses, they feel it is more likely that these plastic particles act in synergy with other factors driving ill health, exerting an additional toll on the body's systems over the course of many years.

"It's not asbestos," Fay Couceiro, professor of environmental pollution at the University of Portsmouth in the UK, says of the microplastics in our bodies. "They're not going to immediately cause a specific harm, but it's more likely that they're going to damage your cells and create a burden on your overall wellbeing which makes you more likely to get illnesses."

One of the unique challenges with attempting to link microplastics with chronic diseases, compared with other well-known risk factors, such as excess red meat or saturated fat, is that this single term encompasses a world of almost infinite complexity. Studies on bottled water, for example, have found that a single litre can contain as many as 240,000 different plastic particles of varying dimensions and materials. Among them, researchers identified no less than seven different categories of plastic, ranging from a form of nylon called polyamide to polystyrene.

"There are numerous types of plastics, each with different compositions which degrade into various forms and shapes," says Verena Pichler, an associate professor of pharmaceutical chemistry at the University of Vienna, Austria. "The term microplastic doesn't capture the variability of what we're dealing with."

The other challenge for researchers like Pichler is that in different people, various microplastics may be doing very different things. She points out that research has suggested certain plastic particles can absorb environmental toxins and carry heavy metals, while various chemicals added to plastic may interact with the network of hormones in the body. Nanoplastics (plastic particles which are less than one micrometre ins size), much smaller than microplastics which are five millimetres or less in length, may be even more damaging as they are small enough to be able to cross cellular membranes and gather within cells.

Some microplastics have also been found to act as a hub for so-called antimicrobial resistance genes, which can then interact with bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites to confer resistance against drugs. Couceiro is currently leading a project in Antarctica, collecting samples from the large quantities of wastewater discharged into the ocean from cruise ships, with the aim of better understanding the types of microplastics which tend to harbour these genes.

"It sounds like a weird place to do this, but Antarctica has the lowest load of antimicrobial resistance genes so it's a good area to look at that because you don't have so much noise from other things," says Couceiro.

Raffaele Marfella, professor of internal medicine and microplastics researcher at the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli in Naples, says that he suspects both microplastics and nanoplastics could be driving accelerated ageing. Marfella believes that they could be achieving this in several ways, including inducing blood vessel dysfunction, creating a growing burden of chronic low-grade inflammation, as well as altering cell behaviour in internal organs through the generation of DNA-damaging molecules called reactive oxygen species. This inflammatory response has already been identified in seabirds leading to a condition which has been dubbed "plasticosis" and Marfella feels it is plausible that this could also be happening in humans.

It's a sentiment shared by Pichler, who was first drawn to this subject area after reading about the high concentrations of microplastics detected in human stool samples, and speculated that they may be linked to the rising prevalence of colorectal cancers. Her subsequent research has raised her suspicions that microplastic accumulation may be involved in elevating cancer risk in some way.

"Studies suggest that microplastics may have a role in amplifying inflammation, which is concerning," says Pichler. "If an inflammatory response persists or is actively promoted by continuous exposure to plastics, this could have implications for tumour formation and disease progression. Although the direct role of microplastics in cancer development is still being investigated, existing scientific databases and studies indicate a probable connection."

Because humans are consuming so many different types of plastic, Wright says that it's both unlikely and impractical, without vast sources of funding, for researchers to be able to identify a direct link between ingesting microplastics and one particular disease. This is unlike an environmental pollutant such as tobacco smoke, which has been shown to be a cause of lung cancer. "The variety of microplastics in the environment means that you just couldn't test every single possibility [in terms of the links between microplastics and disease], because that would be hundreds of experiments to run," Wright says.

Marfella feels that the more pragmatic way forward is to try and identify thresholds for how much our bodies might be able to safely tolerate before the risk for toxicity and damage becomes too high. He says that his team is currently working towards this goal with the help of "vascular organoids" – lab-grown 3D structures made from real human cells, which resemble the blood vessels inside the human body, albeit in a petri dish. The scientists are exposing these artificial blood vessels to different types of plastics and in different doses.

"We don't yet have a definitive threshold for toxicity, but we are starting to see patterns," says Marfella. "For example, preliminary data from animal models suggests that chronic exposure to 10-100 micrograms [10-100 millionths of a gram] of microplastics per kilogram of body weight per day, can induce measurable inflammatory and metabolic changes," he says.

However, so far this research has been conducted on mice, and translating the results to humans is complex, Marfella explains. For example, this could be because of differences in metabolism, clearance mechanisms and sources of exposure, he says.

Couceiro says that the risk may also vary depending on a person's underlying state of health, with older people or those with underlying health conditions being markedly more vulnerable to the effects of microplastics.

Research studies have already suggested that microplastics or nanoplastics ingested by cancer patients may impact treatment success, with these tiny particles capable of altering the behaviour of cancer medicines in the body, for example by binding to these drugs and limiting the amount of the active ingredient that is released into tumours. Now, along with her team at the University of Portsmouth, Couceiro is attempting to understand whether certain doses of microplastics pose a greater risk for people with chronic asthma or other long-term respiratory diseases.

"With asthma, we know that air quality is a massive thing, one of the major problems that initiates attacks," says Couceiro. "And if plastic particles are slightly worse than the other particles in the air, then we need to try and reduce their exposure to them."

To do this, Couceiro is planning to examine samples of phlegm, the thick mucus coughed up from the lungs and airways, to see whether microplastics are present in particularly high quantities when patients are experiencing an exacerbation of their symptoms. She's also visiting the homes of vulnerable patients to measure air quality samples, to get an idea of the types of plastic particles that they're breathing in, and then test the impacts of those particles on samples of their cells.

"If we can do this with enough people, we might be able to draw some general conclusions across a number of people with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and speak to them about what's in their homes and how they can avoid certain things," says Couceiro.

Ultimately, like many researchers in the field of microplastics, Couceiro is hoping to gather enough data so that she can approach plastics manufacturers and make recommendations about how they can make their products safer. For example, a certain type of plastic might seem to be particularly implicated in triggering asthma attacks, or various chemicals in the plastic could be especially prone to leaching out and initiating toxic processes within the body, she says.

"We know that microplastics are everywhere, even in the indoor environment. If they're in your air, you're still taking in microplastics at low levels when you're asleep," says Couceiro. "So we would like, if it's possible, to speak to manufacturers about how to avoid them, whether they can stop making certain plastics in the first place. For example, for people who go into hospital to be treated for respiratory diseases, the masks are plastic, and the tubing is plastic. So can we find better alternatives which prevent them getting into the system in the first place?"

-BBC