I tried buying in bulk to see if it was more sustainable – as well as cheaper

Buying food in bulk can seem like a hassle – but it's not only better for the planet, it'll save you a lot of money too.

You could call it a moment of awakening. I stood in aisle 12 at my Los Angeles grocery store, staring at a bag of organic oats. The oats cost $11.99 (£9.55). They'd probably last my family a week. I'd had enough. I knew oats were not that expensive.

Granted, I was at my local store, a convenient rather than money-conscious choice, but this was ridiculous. I couldn't help but feel I was being scammed by my friendly neighbourhood supermarket.

I swore, there and then, in aisle 12, that I was going to find a way to buy direct from producers and cut out the middle man. I wanted to see what I could buy, how much money I could save – and, as an added bonus, cut down on packaging.

The first thing I did was to write down a list of my most frequently bought dried goods items – I began researching buying dairy direct from source but it got complicated quickly. So I set about researching how to buy oil, oats, rice, mung beans and tea in bulk.

I had to find trustworthy organic sources, research the supply chain – where the seller was based, where they got their produce from, and how they transported it – and then work out the cost, and how each item was packaged. I did my research. A lot of research. Especially when it came to oats.

Saving pennies

It took all my school maths skills to figure out whether the 25lb (11.4kg) bag of organic oats I was about to purchase for $48 (£38.21) was going to be cheaper than $8.99 (£7.16) for 2.6lb (1.18kg). The answer was yes. The bulk bag cost $1.92 (£1.53) per pound, the smaller supermarket bag cost $3.46 (£2.75) per pound. If I had bought 25lb (11.4kg) in supermarket oats I'd have spent $86.50 (£68.86).

Then there was the organic coconut oil: $30.75 (£24.48) for 3.8 litres (1 gallon), compared to $7.49 (£5.96) for 400ml (14.1oz) – I'd have spent $71.15 (£56.64) buying the same amount in individual jars.

The mung beans were also a satisfying success. I usually spent $11.99 (£9.55) on a 2lb (0.91kg) bag. I found a 25lb (11.4kg) bag for $71.75 (£57.11), saving me $78.13 (£62.19). Yes, it would have cost me more than twice as much to buy the same amount of beans in small amounts.

The financial part was easy – yes, it's far cheaper to buy in bulk.

Tracking whether buying in bulk is better for the planet was tough. And I'm not the only one who thinks so.

"From a consumer perspective, determining whether a product is environmentally preferable can be challenging due to the lack of comprehensive information needed to assess its environmental impact," says Valérie Patreau, a doctorate student in sustainable innovation at Polytechnique Montreal in Canada. "While we can gauge its waste-reduction benefits, evaluating its carbon footprint requires more detailed data, typically obtained through life-cycle assessments."

Eventually, I decided to make things as simple as possible. I found one company which sold almost everything I needed for this experiment and I ordered mung beans, powdered dandelion root [which you can use as a tea and coffee alternative], rice and oats. By ordering all these items at once from the same company, I cut down on travel emissions and delivery packaging.

Global food miles account for 19% of food systems emissions, and so it's important to me to buy local wherever possible. The company, called Essential Organics, is headquartered in Washington. But the products came from all over the world. My dandelion tea came from China. The rice from Thailand. Mung beans from India. Coconut oil from the Philippines. Only the oats came from the US. I was never going to be able to work out the carbon count. But then I wouldn't be able to when buying individual items either.

Alannah LaVergne, a spokesperson for the online retailer Essential Organics, says as the company's goal is to encourage bulk buying, they have a higher shipping minimum. "This minimises the product-to-plastic packaging ratio and saves the customer more money per pound," says LaVergne.

Buying in bulk and buying local is rather hard to achieve, and you have to pick your battles when it comes to sustainable shopping. I felt that all in all, if I could order in bulk from the same place at the same time, then I'd have taken all reasonable steps to lower the food's carbon footprint. Although would my carbon footprint have been smaller if I had just bought my oats from the store when I'm heading there anyway? One could spend hours thinking about this.

Beating waste

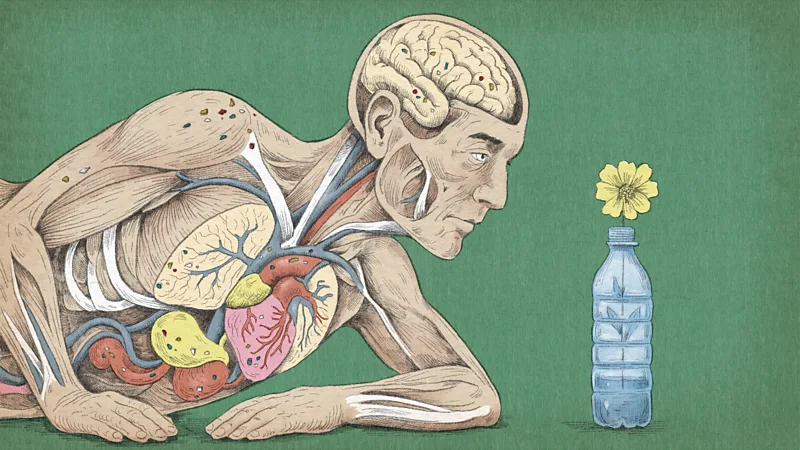

In the US, only 4% of plastic waste is recycled. Globally this number is slightly higher, at 9%. But it's still a worrying figure given how much plastic we consume, and the destructive impact plastic has on our environment.

I wondered if, on top of saving money, whether buying in bulk would reduce waste? Unfortunately, there isn't a lot of research on this specific topic. But one study published in 2023 – which Patreau co-authored – found that US consumers are looking for solutions to reduce waste – particularly plastic waste from single-use packaging.

The travel emissions it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

"An increasing number of scientific studies employing life-cycle assessment methods are evaluating bulk purchasing scenarios," Patreau says. "Many demonstrate that buying in bulk is environmentally advantageous compared to purchasing the same quantity of a product in single-use containers," she says.

But it's the environmental impact which varies between products. "For instance, products requiring extensive cleaning post-use, like yogurt versus nuts, can have different environmental footprints depending on factors like energy sources used for cleaning," says Patreau.

The key, she says, is maximising container reuse.

I had already made the switch to using shampoo and conditioner bars rather than plastic bottles, so I wasn't looking for reusable bathroom products. But I was looking to make my kitchen more sustainable.

The oats came in a very large brown paper bag, which greatly pleased me, as the oats I usually buy either come in a cardboard tub with a plastic lid, or a plastic pouch. So the bulk oats won on both the environment and the price points.

The oil, however, came in a giant plastic tub, whereas the individual jars are glass. (Read about how the environmental credentials of plastic and glass measure up.) But then I went down the rabbit hole of what Los Angeles recycles and well, that's a whole other article. Generally, glass gets recycled more than plastic does – around a third gets a second life.

In the 2023 study, the researchers found most consumers were not willing to pay more for bulk products with reusable packaging. The main barriers to buying in bulk were hygiene concerns, the extra effort involved and limited access. And the main motivators were environmental concerns and financial incentives.

Looking at my newly stocked cupboards, I wondered about other barriers too. Certain dietary habits may be more suited to bulk buying than others, for instance. As someone who does a lot of cooking from scratch, eats generally low-processed food and uses lots of plant-based ingredients, this form of shopping suited me and my eating habits well. But, clearly, mung beans aren't to everyone's taste. And while it may work out cheaper overall, investing a large lump sum of money up front for food isn't always going to be possible for people on restricted budgets.

There's limited information on the benefits of bulk buying, Patreau adds. We often assume it's better for the environment, but it's difficult to understand the full impacts without knowing the full life-cycle of the product – from production to post-consumption. In order for us to be more willing to buy in bulk, Patreau explains, we simply need more information.

-bbc