'Human stories are always about one thing – death': Why the shadow of death and WW1 hang over The Lord of the Rings

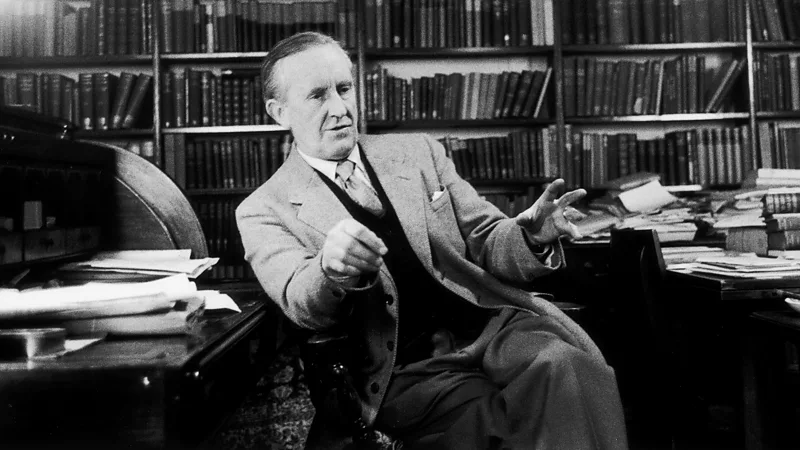

In a 1968 interview, the BBC spoke to author JRR Tolkien about his experiences during World War One, how they had a profound effect and influenced his epic fantasy novel, Lord of the Rings.

"Stories – frankly, human stories are always about one thing – death. The inevitability of death," The Lord of the Rings author JRR Tolkien told a BBC documentary in 1968, as he tried to explain what his fantasy magnum opus was really about.

The novel, the first volume of which was published 70 years ago this week, has enthralled readers ever since it hit the shelves in 1954. The Lord of the Rings, with its intricate world-building and detailed histories of lands populated with elves, hobbits and wizards, threatened by the malevolent Sauron, had, by the time of the interview, already become a bestseller and a cornerstone of the fantasy genre.

To better explain what he meant by the story being about death, Tolkien reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out his wallet, which contained a newspaper clipping. He then read aloud from that article, which quoted from Simone de Beauvoir's A Very Easy Death, her moving 1964 account of her mother's desire to cling to life during her dying days.

"There is no such thing as a natural death," he read. "Nothing that happens to a man is ever natural, since his presence calls the world into question. All men must die: but for every man his death is an accident and, even if he knows it and consents to it, an unjustifiable violation."

"Well, you may agree with the words or not," he said. "But those are the key-spring of The Lord of the Rings."

The spectre of death had loomed large over Tolkien's early life and those experiences had profoundly shaped the way he saw the world, influencing the themes that he would repeatedly revisit when writing his tales of Middle-earth.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in 1892 to "two, very English, extremely British parents" in South Africa, where they had moved, while his father pursued a career in banking.

When he was three, during a visit home to see his English family with his mother and his younger brother Hilary, his father – who had planned to join them – unexpectedly died of rheumatic fever. Being the breadwinner, his sudden death rendered the family destitute. His mother, Mabel, decided to stay in the UK, settling in a cheap cottage in the village of Sarehole, near Birmingham.

His return to England was "a kind of double coming home, which made the effect of the ordinary English meadows, countryside breaks, immensely important to me," Tolkien told the BBC.

The mixture of the countryside of the surrounding area and the industrialised nearby Birmingham went on to heavily influence the landscapes he later conjured up in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien was extremely close to Mabel, who taught her sons at home and awakened in him a love of storytelling, myths and botany. She nurtured his remarkable gift for languages, schooling him in Latin, French and German at an early age, and inspiring him to invent his own languages later purely for enjoyment.

When he was 12, Mabel was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, which before the discovery of insulin in 1921, proved to be a fatal prognosis. Tolkien's mother had converted to Catholicism at the turn of the century, and when she died on 14 November 1904, the two orphaned boys were left in the custody of a priest, Father Xavier Morgan, and then with an aunt.

Tolkien's academic prowess secured him a place at Oxford University, where he studied classics before switching to philology because of his talent for languages. When World War One broke out in 1914, he managed to defer enlisting due to his studies. But upon his graduation the following year and faced with increasing social pressure from relatives, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers and shipped off to the Western Front.

'Mud, chaos and death'

Tolkien's battalion arrived at the Somme in early July 1916. The battle would prove to be one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history. The brutal horror of the trench warfare he endured there, with its mud, chaos and death, left an indelible mark on him, and went on to permeate his later writing.

He'd lost two of his dearest friends on the Somme and, you can imagine, he must have been inside as much of a wreck as he was physically – John Garth

The war-ravaged battlefields of France and Belgium can be seen in his descriptions of the hellish, desolate landscape of Mordor in The Lord of the Rings. Echoes of the immense suffering and carnage he witnessed – wrought by the new mechanised warfare – can be found in his portrayal of the terrifying orcish war machines and the corrupted wizard Saruman's deforestation of Middle-earth.

Author of the book Tolkien and the Great War, John Garth, told the BBC in 2017 that he believed the novelist used his writing like an "exorcism" of the horrors he saw in WW1. Trench fever was not the only way in which the war affected the novelist, he suggests. "He'd lost two of his dearest friends on the Somme and, you can imagine, he must have been inside as much of a wreck as he was physically," he said.

That belief is shared by Dr Malcolm Guite, poet and theologian. He told the BBC Great Lives podcast in 2021 that "there are details which I think come straight from his war experience, and which he probably couldn't have written directly [afterwards]. He was traumatised. So, the dead bodies in the pools in the marshes looking up. The terrible waste in front of Mordor with the poisonous fumes coming out of the earth. That's all out of the Western Front."

Similarly, Tolkien's experience of the deep camaraderie formed between soldiers enduring such atrocities adds subtle, meaningful realism to the unwavering bond between the two leading hobbits in The Lord of the Rings, Sam and Frodo.

"Tolkien specifically said that was the relationship of those young officers who were slaughtered, and their batman [a soldier assigned to an officer as a personal servant] as they were called," said Guite.

In November 1916, after months of battle, Tolkien contracted trench fever, a disease caused by lice, and he was invalided back to England. By the end of the war, almost all of the people he had served with in his battalion had been killed.

While Tolkien's wartime experiences may have added depth and authenticity to the mythological world he created, the author himself always maintained that he did not write The Lord of the Rings as an allegory for WW1, or indeed any other specific event from history.

"People do not fully understand the difference between an allegory and an application," he told the BBC in 1968.

"You can go to a Shakespeare play and you can apply it to things in your mind, if you like, but they are not allegories... I mean many people apply the Ring to the nuclear bomb and think that was in my mind, and the whole thing is an allegory of it. Well, it isn't."

But part of the enduring appeal of The Lord of the Rings is that it is more than merely a direct allegory. The themes it explores – war and trauma, industrialisation and the despoiling of the natural world, the corrupting influence of power and how the bond of friendship can help people endure adversity and loss – resonate far beyond a single event or time.

The fantasy novel has, at times, been dismissed by some critics as just an adventure story of valiant friends battling an unspeakable evil. But The Lord of the Rings is not a glorification of war – it is a reflection on how death and the trauma of conflict irrevocably changes those who witness and live through it.

The dislocation felt by many soldiers who served in WW1 on their return home, greeted by those who were unable to comprehend what they had seen and done, is mirrored in the last book when the hobbits return to the Shire. They find their world changed in the aftermath of the battle, with their fellow hobbits unable to fathom why Frodo and Sam, who are haunted by what they have been through on their journey, can never be that innocent again.

"One reviewer once said it was a very jolly book, isn't it?" Tolkien said to the BBC. "All the right boys come home and everybody is happy and glad. It isn't true, of course. He couldn't have read the story."

-BBC