Iran's abandoned bases in Syria: Years of military expansion lie in ruins

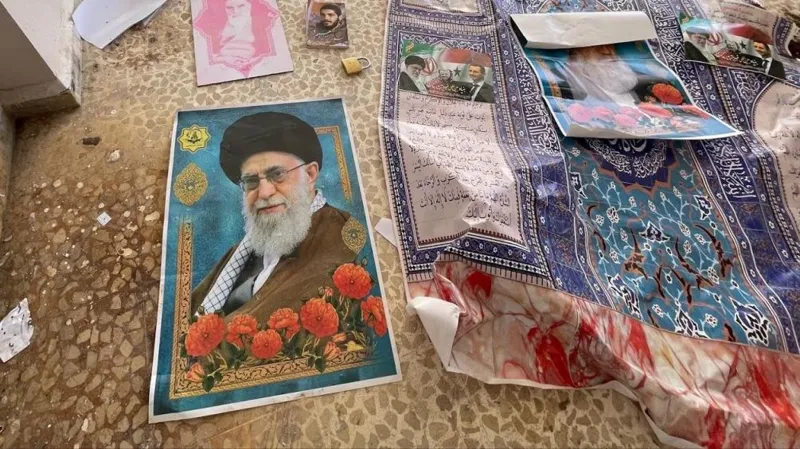

Mouldy half-finished food on bunk beds, discarded military uniforms and abandoned weapons - these are the remnants of an abrupt retreat from this base that once belonged to Iran and its affiliated groups in Syria.

The scene tells a story of panic. The forces stationed here fled with little warning, leaving behind a decade-long presence that unravelled in mere weeks.

Iran was Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's most critical ally for more than 10 years. It deployed military advisers, mobilised foreign militias, and invested heavily in Syria's war.

Its elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) built deep networks of underground bases, supplying arms and training to thousands of fighters. For Iran, this was also part of its "security belt" against Israel.

We are near Khan Shaykhun town in Idlib province. Before Assad's regime fell on 8 December, it was one of the key strategic locations for the IRGC and its allied groups.

From the main road, the entrance is barely visible, hidden behind piles of sand and rocks. A watchtower on a hilltop, still painted in the colours of the Iranian flag, overlooks the base.

A receipt notebook confirms the base's name: The Position of Martyr Zahedi - named after Mohammad Reza Zahedi, a top IRGC commander who was assassinated in an alleged Israeli airstrike on Iran's consulate in Syria on 1 April, 2024.

The supplies recently ordered - we found receipts for chocolates, rice, cooking oil - suggest daily life continued here until the last moments. But now the base has new occupants - two armed Uyghur fighters from Hayaat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Islamist militant group whose leader Ahmed al-Sharaa has become the new interim president of Syria.

The Uyghurs arrived suddenly in a military vehicle, asking for our media accreditation.

"Iranians were here. They all fled," one of them says, speaking in his mother tongue, a dialect of Turkish. "Whatever you see here is from them. Even these onions and the leftover foods."

Boxes full of fresh onions in the courtyard have now germinated.

The base is a labyrinth of tunnels dug deep into white rocky hills. There are bunk beds in some rooms with no windows. The roof of one of the corridors is draped in fabric in the colours of the Iranian flag and there are a few Persian books on a rocky shelf.

They left behind documents containing sensitive information. All in Persian, they have details of fighters' personal information, military personnel codes, home addresses, spouses' names and mobile phone numbers in Iran. From the names, it's clear that several fighters in this base were from the Afghan brigade that was formed by Iran to fight in Syria.

Sources linked to Iran-backed groups told BBC Persian that the base houses mainly Afghan forces accompanied by Iranian "military advisers" and their Iranian commanders.

Tehran's main justification for its military involvement in Syria was "to fight against jihadi groups" and to protect "Shia holy shrines" against radical Sunni militants.

It created paramilitary groups of mainly Afghan, Pakistani and Iraqi fighters.

Yet, when the final moment came, Iran was unprepared. Orders for retreat reached some bases at the very last moment. "Developments happened so fast," a senior member of an Iran-backed Iraqi paramilitary group tells me. "The order was to just take your backpack and leave."

Multiple sources close to the IRGC told the BBC that most of the forces had to flee to Iraq, and some were ordered to go to Lebanon or Russian bases to be evacuated from Syria by the Russians.

An HTS fighter, Mohammad al Rabbat, had witnessed the group's advance from Idlib to Aleppo and Syria's capital Damascus.

He says they thought their operation would take "about a year" and best, they'd "capture Aleppo in three to six months". But to their surprise, they entered Aleppo in a matter of days.

The regime's rapid downfall was brought about by a chain of events after Hamas's 7 October attack on Israel.

That attack led to an escalation of Israeli air strikes against the IRGC and Iran-backed groups in Syria and a war against another key Iranian ally – the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, whose leader was killed in an air strike.

This "situation of psychological collapse" for Iran and Hezbollah was central to their downfall, says 35-year-old fighter Rabbat.

But the most crucial blow came from within: there was a rift between Assad and his Iran-linked allies, he says.

"There was a complete breakdown of trust and military co-operation between them. IRGC-linked groups were blaming Assad of betrayal and believing that he is giving up their locations to Israel."

As we pass through Khan Shaykhun, we come across a street painted in the colours of the Iranian flag. It leads to a school building that was being used as an Iranian headquarters.

On the wall at the entrance of the toilets, slogans read: "Down with Israel" and "Down with the USA".

It was evident that these headquarters were also evacuated at short notice. We found documents classified as "highly sensitive".

Abdullah, 65, and his family are among the very few locals who stayed and lived here alongside the IRGC-led groups. He says this life was hard.

His house is only a few metres away from the headquarters and in between, there are deep trenches with barbed wire.

"Movement at night was prohibited," he says.

His neighbour's home was turned into a military post. "They sat there with their guns pointing at the road, treating us all as suspects," he recalls.

Most of the fighters didn't even speak Arabic, he says. "They were Afghans, Iranians, Hezbollah. But we referred to them all as Iranians because Iran was controlling them."

Abdullah's wife Jourieh says she is happy that the "Iranian militias" have left, but still remembers the "stressful" moment before their withdrawal. She had thought they would be trapped in crossfire as Iran-backed groups were fortifying their positions and getting ready to fight, but then "they just vanished in a few hours".

"This was an occupation. Iranian occupation," says Abdo who, like others, has just returned here with his family after 10 years. His house had also become a military base.

I observed this anger towards Iran and a softer attitude towards Russia in many conversations with Syrians.

I asked Rabbat, the HTS fighter, why this was.

"Russians were dropping bombs from the sky and other than that, they were in their bases while Iranians and their militias were on the ground interacting. People were feeling their presence, and many weren't happy with it," he explained.

This feeling is reflected in Syria's new rulers' policy towards Iran.

The new authorities have put a ban on Iranian nationals, alongside Israelis, entering Syria. But there is no such ban against Russians.

Iran's embassy, which was stormed by angry protesters after the fall of the regime, remains closed.

The reaction of Iranian officials towards developments in Syria has been contradictory.

While supreme leader Ali Khamenei called on "Syrian youths" to "resist" those who "have brought instability" to Syria, Iran's foreign ministry has taken a more balanced view.

It says the country "backs any government supported by the Syrian people".

In one of his first interviews, Syria's new leader Sharaa described their victory over Assad as an "end of the Iranian project". But he hasn't ruled out having a "balanced" relationship with Tehran.

For the moment, though, Iran is not welcome in Syria. After years of expanding its military presence, everything Tehran built is now in ruins, both on the battlefield and, it seems, in the eyes of a large part of Syria's public.

Back at the abandoned base, Iran's military expansion was still under way even in the last days. Next to the camp were more tunnels under construction, apparently the beginnings of a field hospital. The cement on the walls was still wet and the paint fresh.

But left behind now is evidence of a brief fight - a few bullet shells and a military uniform covered with blood.

-BBC