Last male of his kind: The rhino that became a conservation icon

Sudan, the world's last male northern white rhino, died in 2018. In his final years, he became a global celebrity and conservation icon, helping raise awareness about the brutality of poaching.

There was a lot of hope riding on Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros. He was labelled the "world's most eligible bachelor" by the dating app Tinder, the "most famous rhino" by various news outlets and a "gentle giant" by the armed guards who watched over him 24-hours-a-day. But Sudan's life carried the baggage of a species decimated by poaching.

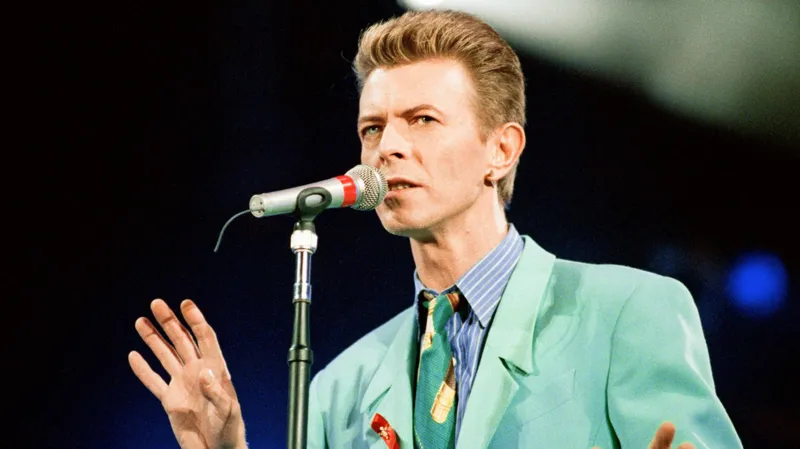

In the Ol Pejeta conservancy at the foot of Mount Kenya, AFP photojournalist Tony Karumba captured a celebrated snapshot of Sudan on 5 December 2016, approximately 15 months before the rhino's death.

At the forefront of Karumba's image is the tender relationship between the humans at the conservancy and Sudan. The photo is iconic but not iconoclastic, exemplifying an ordinary moment of the all-too-late-yet-genuine care that northern white rhinos received from the species that decimated them. Once lost, gone forever, only to live in photos like Karumba's photo series.

As Sudan was released from his pen to pasture, Karumba captured his pictures. "There's trust and love all over that moment," says Karumba. "Being in Sudan's presence always felt for me like a visit with a sage; his demeanour, despite his behemoth self, had a way of conveying a calm patience with me and though his minders would always be hovering just outside my camera's frame, he [Sudan] was accepting of my wary intrusions and poised as though he was aware of his symbolism as the last icon of his subspecies."

The photo showcases Sudan's craniate profile and his two horns, a trait characterising the white rhino subspecies, shaved off to deter poachers. Sudan's carer calms the two-and-a-half-tonned (2,500 kg)animal, whose head is longer than the man's torso. Karumba's vantage, his low viewpoint on Sudan, "emphasised the power and the stature of the rhino," says Michael Pritchard, programmes director at the Royal Photographic Society in the UK.

"The power of this photograph is the interaction between this impressive animal and this human," says Pritchard. "There's a kindness, a relationship."

Sudan spent most of his life at the Safari Park Dvůr Králové in the Czech Republic from 1975 to 2009. He was then moved to the highly surveilled Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Laikipia, Kenya, which was a last-ditch effort to encourage procreation with the remaining females of his subspecies. It didn't work.

Sudan died on 19 March 2018, age 45, crushing hopes of saving the northern white rhinos from extinction. Only two female northern white rhinos – both former zoo animals called Najin and Fatu – remain alive at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. Both are incapable of sustaining a pregnancy and the subspecies is now "functionally extinct". But there is now new hope that it might be possible to resurect the northern white rhino after scientists have achieved the world's first IVF pregnancy in a closely-related subspecies, the southern white rhino. They hope to repeat this with northern white rhinos next. (Read more about the achievement from BBC News.)

"We are very confident that we will be able to create northern white rhinos in the same manner and that we will be able to save the species," Susanne Holtze, a scientist at Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Germany, which is part of the Biorescue project, a consortium working to save the white rhino species, told BBC News.

Sudan was accepting of my wary intrusions and poised as though he was aware of his symbolism as the last icon of his subspecies – Tony Karumba

"Sudan was one of those news stories that went around the world," says Pritchard. "His photos show that we're changing the world in a way that numbers, statistics or government meetings can't do. That's the power of photography: to engage with a public that might not respond to facts and figures."

The photos themselves are "straightforward," Pritchard continues. But it's the context around the photographs that struck him. Sudan's story became much bigger than Sudan.

"We're looking at something that is no longer with us both on an individual level but, more importantly, on a species level," says Pritchard.

Once the world caught a glimpse of the functional face of extinction, it could not get enough. Sudan's publicity campaign won him fans around the globe, visits from tourists and donations for conservation efforts. When news of his passing spread, politicians and celebrities posted pictures of themselves meeting Sudan. On 20 December 2020, Google launched a Doodle on its homepage in remembrance of Sudan, who casts a long shadow in the illustration, which appeared in the search bars of every continent except Antarctica.

"It leaves me happy and feeling accomplished that my efforts to document the glimpses I had of Sudan were and still are so well received," says Karumba. "Repeatedly, our coverage of Sudan seemed to create a buzz, garnering interest from mainstream media and conservation circles."

Sudan – and his ageing likeness – showed people how vulnerable rhinos are, says Karumba, who interacted with Sudan throughout his final decade at the Kenyan conservancy.

Rhinos, the biological equivalent of armour-plated tanks with an anachronistic dinosaurian demeanour, are deceptively docile.

"I remember being surprised at how calm he was, as I snapped photos of him and the females back then," Karumba wrote of his first encounter with Sudan. "We were hustling and bustling all around him and climbing on his crate to try and get a good picture. But he was completely calm."

WHY ARE NORTHERN WHITE RHINOS EXTINCT IN THE WILD?

Illegal poaching, fueled by the increasing demand for keratin-rich rhino horn in traditional medicinal practices, has devastated the African rhino population. In 1960, there were still 2,360 wild northern white rhinos but by 2008 the subspecies was extinct in the wild.

From beyond the grave, Sudan went from a representative of optimism to a cautionary tale, cemented in conservation iconography, says sustainability economistat the University of Oxford Michael 't Sas-Rolfes. When Sas-Rolfes met Sudan in Kenya at an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) African Rhino Specialist Group meeting towards the end of the rhino's life in 2013, "it was like the walking dead".

Rhinos are what Sas-Rolfes calls a "charismatic" endangered species. Other charismatic examples include elephants, big cats and bears, which all capture the public's imagination, he says. Charismatic wildlife walks the fragile line between being revered and feared, hoisted by attention from economically developed countries.

Look no further than branding to see charismatic wildlife take the stage. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, emergent international wildlife non-profits like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) launched its Save the Rhino campaign, says Sas-Rolfes.

"Our relationship with charismatic wildlife is complex, but they've always been held in high esteem," he says. "NGOs have capitalised on the powerful imagery to raise funds."

William Fowlds, a wildlife veterinarian and conservationist, has first-hand witnessed the bloody repercussions of poaching in South Africa, which is home to more rhinos than any other country. In 2022, 448 rhinos were illegally killed, compared to 451 in 2021 in South Africa, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The amount of brutality afflicted against the rhino depends on the experience-level of the poacher, who typically uses a saw or a machete to hack its horn off, Fowlds says. "Pieces of face and flesh fly off its body, landing multiple metres away from the rhino, blood splattering on vegetation around," he says. "You can see by the marks on the ground where the animal tried to get away."

One word springs to mind when Fowlds looks at the photo of Sudan: loneliness.

"We've invaded their world. We've destroyed their habitat. We've separated them from each other. Now, we've arrived at a time when there are very few of them left on the planet," he says.

The power of this photograph is the interaction between this impressive animal and this human. There's a kindness, a relationship – Michael Pritchard

Rhinos are social and soft-natured, Fowlds says. Intelligent, too, with varied personalities.

"Like Sudan's handler in this picture, people who see the photo feel up close and are privileged to spend time with the last of his kind," Fowlds says. "They're vulnerable. Obviously, the numbers at the hands of humans reflect that."

Fowlds brings up another famous, albeit happier, rhino story. Her name is Thandi, a female southern white rhino who was disfigured by poachers on 2 March 2012. Two other rhinos were attacked, both died. Thandi improved – much to the surprise of veterinarians involved, like Fowlds. After this rescue and rehabilitation, she has gone on to give birth to multiple babies and wears her facial scars with pride.

CARBON COUNT

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

Sudan and Thandi have phenomenal stories, Fowlds says. Both of their faces are important in the fight against poaching. They represent the first step of awareness.

"They inspire many people, including myself, to do more for rhinos," Fowlds says. "When you see a creature like that fighting to survive, we realise we should get behind them and fight just as hard."

The story of rhino poaching is evolving – and extremely human, says US-based rhino conservation specialist Katie Lawton. The easiest comparison is narcotics or arms trafficking, Lawton says. A rhinoceros horn is more valuable by weight than gold, diamonds or cocaine. Wildlife crime is a big business.

Subsistence poachers, driven by poverty and hunger, are paid to poach by commercial, syndicate organisations. Targeting the individual subsistence poachers doing the dirty work will not address the systemic framework of demand, Lawton says.

It's easy for audiences from industrialised nations to see the issue of poaching from an unconsciously colonial lens and expect governments to solve the issue, Fowlds says. But the crisis here is deep-rooted, historical and socio-economic.

"The problem with endangered species like rhinos is that you don't have time to fix those long-game problems, because there will be no rhinos left by the time you have changed those socio-economic circumstances," Fowlds says.

Under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (Cites), global trade of rhino horns has been banned since 1977. However, countries like South Africa have overturned the ban to allow domestic trade, based on commercial rhino breeders' argument that legal trade would prevent poaching.

"Symbolically, Sudan made me think, 'I don't want it to get to that point,'" Lawton says. "And it won't, ever again."

Overall, rhino poaching rates have declined since 2018, when Sudan died. Trade data indicates the lowest annual estimate of rhino horns entering illegal trade markets since 2013.

The combination of conservation and biological management initiatives resulted in a total of 6,487 black rhinos in all of Africa. There are now 16,803 white rhinos on Earth, all except two are southern white rhinos. The first viable IVF pregnancy in a southern white rhino has raised hope that these animals could be brought back from the brink.

"That picture of Sudan encapsulates the relationship between the animal kingdom and mankind," says Pritchard. "Perhaps the negative side, but also there's a positive relationship between man and rhinos that we should all be striving for. Ultimately, I see it as a positive picture."

"Sharing these moments of the very special environment that our planet is blessed with is a motivation to keep venturing into the wonders of nature's wilds, showing the characters in it that make it worth experiencing and preserving," says Karumba.

-bbc