Sweden has long opposed nuclear weapons – but it once tried to build them

In the years after World War Two, neutral, peace-loving Sweden embarked on an ambitious plan – build its own atomic bomb.

Sweden hasn't fought a war since 1814. But for more than 20 years after the end of World War Two, this formerly neutral northern European country pursued a plan to equip its military with the ultimate weapon, the atomic bomb. The government finally shut the programme down in 1968 after a long public debate.

Sweden thereby joined a unique club of nations – which includes Switzerland, Ukraine and South Africa – who gave up their nuclear weapons programmes and showed the world that nuclear disarmament was possible.

The extent of Sweden's nuclear programme was "uncomfortable" for politicians keen to burnish the country's new anti-nuclear credentials, until journalist Christer Larsson discovered the truth in 1985 and forced the nation to confront its secret nuclear history.

The veil of secrecy around the history of the programme fuelled speculation that Sweden still had a top-secret plan to build its own nuclear weapons.

Decades later, Sweden is now ending 200 years of neutrality and joining the nuclear-armed Nato alliance in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Why did it want to build nuclear weapons in the first place? Why did it stop?

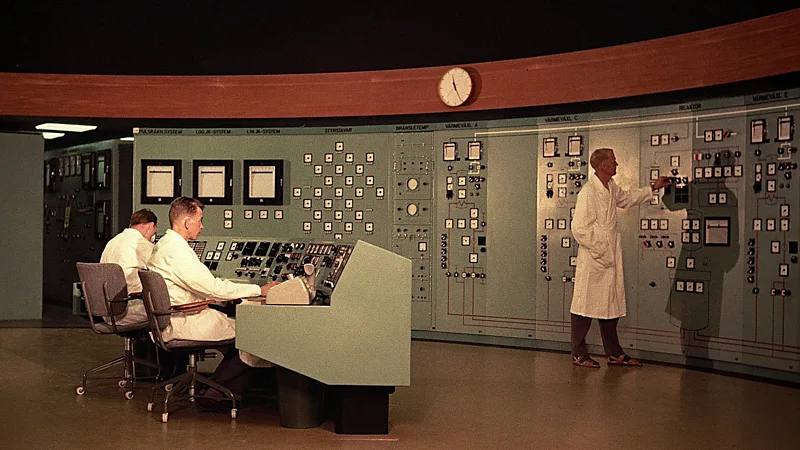

In Ursvik, a quiet suburb of Stockholm, there is a large school building that looks more like a secret research institute – because that's what it once was. The headquarters of the former Swedish National Defence Research Institute (FOA) is one of the few physical remains left of Sweden's nuclear weapons programme.

The supreme military commander of this fiercely independent nation asked for the newly-founded FOA to prepare a report in secret on the feasibility of Sweden building its own atomic bombs two weeks after the reports – and pictures – of the devastated cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki reached Stockholm in 1945.

Sweden may have been a neutral country, but it was a nation whose leaders believed in an armed neutrality – that the price of neutrality was a strong military – and its leadership understood that tactical atomic bombs for use on the battlefield might be needed in the future to preserve that neutrality. The country's long coastline and small population made the country "easy prey" for an opponent such as the neighbouring USSR.

The Nordic country had its own uranium deposits, albeit low-quality ones. It was a prosperous country with a healthy infrastructure thanks to its neutrality during World War Two. The plan to build an atomic bomb wasn't as far-fetched as it might sound today.

Three years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Negasaki, in 1948, the FOA established "the Swedish line" for Sweden to produce a plutonium-based atomic bomb without the need for foreign assistance. Their plan was that plutonium would be acquired through the fission of Swedish uranium in Swedish nuclear reactors with heavy water.

Still operating under a cloak of secrecy, Swedish scientists were forced to slowly, and expensively, start from scratch, because of the lack of a supply of high-grade uranium, and no sharing of information with the United States. The decision was also made to tie the nuclear weapon programme to the civilian programme as a matter of necessity – and disguise its true nature.

"So, we had everything in place to produce weapons-grade plutonium," says Thomas Jonter, author of The Key to Nuclear Restraint: The Swedish Plans to Acquire Nuclear Weapons During the Cold War. The plan included two reactors. "One, Ågesta, a heavy-water reactor south of Stockholm, and another, Marviken, built outside the city of Norrköpin but never put into production and the idea was to build 100 tactical weapons," says Jonter.

"We knew exactly how it should be done. We had everything except the reprocessing facility and the weapons carrier system."

The slow pace of the weapons programme, however, would ultimately be its downfall.

There had been no public debate about the plans, for the simple reason that their existence was known only to a small circle of politicians, high-ranking military officers and scientists (and, presumably, Soviet spies). That secrecy ended in 1954, when the Swedish commander-in-chief, Nils Swedlund, revealed the programme's existence and argued that these weapons were needed to defeat a Soviet invasion.

In April 1957, the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) judged Sweden as having "a sufficiently developed reactor program to enable it to produce some nuclear weapons within the next five years", an assessment that soon cut the timeline to four years.

At the time Sweden's prime minister was Tage Erlander, who had a physics background, and he made sure he regularly talked to world-leading physicists about atomic bombs, including Nobel laureate Niels Bohr. The Danish physicist, who made some brilliant early contributions to nuclear physics, and was smuggled out of German occupied Denmark in WW2 to join the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bomb. The more the prime minister talked, the more he wavered in his support for the nuclear weapons programme, and seeking consensus he repeatedly postponed the final decision until the outcome of arms control talks between the US and the Soviet Union were known.

The Social Democrat women came out very early arguing that Sweden should not acquire nuclear weapons – Emma Rosengren

His principled stand – or shrewd political move, depending on who you believe – allowed critics of the nuclear weapons plan to take centre stage. Many of whom were women. The Federation of Social Democratic Women (Sveriges Socialdemokratiska Kvinnoförbund, SSKF), led by Inga Thorsson, says Jonter, "became the strongest voice against nuclear acquisition".

"The Social Democrat women came out very early arguing that Sweden should not acquire nuclear weapons and for many different reasons," says Emma Rosengren, a researcher (PhD) in international relations at Stockholm University. "Rather than providing protection, these weapons might actually make Sweden a target. So it would decrease rather than increase security.

"They also argued that it would be completely immoral, given the humanitarian consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. So, a peaceful country like Sweden could never contribute to the kind of suffering caused by nuclear weapons."

The contribution of women such as Thorsson to the debate was often not welcome. "They were dismissed as being basically emotional women who should not speak about things they didn't understand," says Rosengren. "And defence policy was very much considered something that at the time only men were capable of dealing with."

The women of the SSKF were soon joined by other groups, such as the Action Group Against Swedish Nuclear Weapons (Aktionsgruppen Mot Svensk Atombomb, AMSA) – and public opinion began to shift.

It was a shift helped by the collapse of the military's support for the weapons they had once championed. The Swedish army, air force and navy had realised just how expensive they were, and cuts in all three services would be needed to pay for them.

The negative attitude of the US to the Swedish nuclear plans was also important, given the growing defence cooperation between the two countries in other areas, including adjusting Swedish airfields to accommodate American bombers.

There was a growing belief among the Swedish elite that Sweden didn't need to develop its own nuclear weapons

The Swedish armed forces and civilian nuclear power programme came to rely on American technology for such things as missile systems, the design of new light water civilian nuclear reactors, data, and even nuclear fuel, which actually made Sweden's pursuit of its own nuclear weapons more difficult. At one point Sweden even explored purchasing American nuclear weapons.

There was also a growing belief among the Swedish elite that Sweden didn't need to develop its own nuclear weapons because the country was under the US nuclear umbrella even though it wasn't actually a member of Nato.

"It's very important to stress there was no kind of formal agreement," says Jonter. "I have read the prime minister's diary, and he doesn't mention it anywhere because it would have been very difficult for either side to sign such an agreement."

Alamy Alva Myrdal was a prominent figure in Sweden's nuclear disarmament movement (Credit: Alamy)Alamy

Alva Myrdal was a prominent figure in Sweden's nuclear disarmament movement (Credit: Alamy)

What he did find were American policy documents that stated the US would "be prepared to come to the assistance of Sweden as part of a Nato or UN response" to Soviet aggression.

"But for such an understanding to actually mean something, it has to be formalised," says Rosengren. But Jonter’s research has not found evidence of any such agreement.

During the 1960s, Sweden – led by politician and diplomat Alva Myrdal – became heavily involved in international efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, which reinforced the campaign against Sweden's own weapons; even supporters of the original plan now only wanted research to continue, not production.

This shift was reflected in public opinion. In 1957, 40% of the public supported the acquisition of nuclear weapons, with 36% against it and 24% unsure. Eight years later, only 17% were in favour, with 69% against and 14% unsure.

One lesson is that to produce nuclear weapons is not that easy – Thomas Jonter

So it was no surprise when, in 1966, the Swedish stopped planning for the production of nuclear weapons, nor when it signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1968 and parliament voted to end the programme altogether, even if limited research carried on into the 1970s.

Jonter highlights that Sweden’s experience can act as a lesson in today’s world

"One lesson is that to produce nuclear weapons is not that easy,” says Jonter, “even if a country already has a domestic nuclear infrastructure. It's very complicated.”

This means a country that wants nuclear weapons may have to cooperate with other technologically more advanced nations, which can create dependency. Then there is the importance of allowing enough time for a public debate so that citizens can really understand what it means if their country acquires nuclear weapons. "I think that's one really important lesson," says Rosengren.

Of course, just because there are lessons to be learned doesn't mean political leaders will change their behaviour. "Unfortunately," Jonter wrote in Physics Today in 2019, "the US decision to withdraw from a nuclear deal with Iran suggests that President Trump and his advisers had not learned this…[first] lesson."

In 2012, Sweden transferred the last plutonium produced for its nuclear weapons programme to the United Sates.

"There was some kind of discussion in the 1960s about having a reserve option, but as far as we know the programme was phased out," says Jonter. "Of course, it's secret, but politically it would be impossible for a party to argue for the manufacture of nuclear weapons."

Rosengren is more blunt. "There is no material left and no political will. We don't produce nuclear weapons."

-bbc