The German robots hunting the sea for WW2 bombs

More than 1.6 million tonnes of unexploded weapons litter the North Sea and Baltic Sea. Remote-controlled seabed crawlers and robots with "smart grabbers" are now cleaning up these toxic munitions.

A boxy robot crawls across the seabed off northern Germany, reaches through the murky water with a metal claw, and picks up its target: a rusting grenade, dumped into the sea after World War Two. Overhead, another robot swims along the surface, scanning the seabed for more munitions. More robot claws reach into the water from above, plucking bombs and mines from the sediment.

A pilot project backed by the German government will be deploying these and other technologies in a bay in the Baltic Sea this summer, to test a fast, industrial-scale process for clearing dumped munitions that are polluting the North and Baltic Seas. The project is part of a wider €100m (£84.6m/$106.9m) programme by the German government that aims to develop a way to safely remove and destroy munitions littering the German parts of the North and Baltic Seas – a toxic legacy that amounts to an estimated 1.6 million tonnes of dumped explosives and weapons.

"The problem is that in every marine area where there was a war, or is a war, there's munitions in the sea. And when it's there for a long time, it can release carcinogenic substances" and other toxic materials, says Jens Greinert, a professor for deep sea monitoring at Christian-Albrecht University in Kiel, Germany, who works at Geomar Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel and is one of the scientists supporting the project. This interactive map illustrates where dumped conventional or chemical munitions have been found.

"These munitions are rusting, and our research has shown that over time, they're releasing more and more carcinogenic [and other toxic] substances, traces of which have been found in fish and mussels," Greinert says. "The longer we wait, the more they're going to rust, and the concentration of harmful substances in the water is going to rise. So now is the moment to figure out what to do with this stuff, while the munitions are still intact enough to be grabbed."

Based on the scientific findings regarding the rusting, leaking munitions, Germany decided it was time to try and remove it from the sea at scale. "Our starting point was to ask, what do we need to do to achieve a healthy marine ecosystem?" says Heike Imhoff, a marine conservation expert at Germany's environment ministry, which oversees the programme. The long-term goal is to build an offshore platform where the munitions can be destroyed in a detonation chamber, after they are retrieved from the sea in a robot-assisted process, she says.

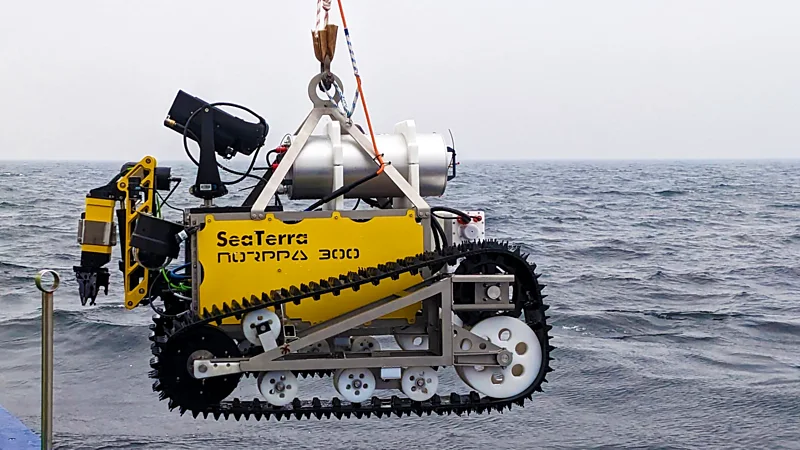

So far, people have tended to take a piecemeal approach to removing unexploded ordnance (UXO) from the sea. For example, offshore wind farm developers routinely survey potential sites for bombs or mines, and then avoid or remove them. To avoid endangering human divers, such work increasingly involves swimming, diving or crawling robots. Crewless vehicles are also used in scientific research for ecological monitoring. They include remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), which are swimming or diving vehicles that are remotely operated via a deep-sea cable linked to a ship; and deep-sea crawlers, remotely controlled vehicles that roll across the seabed on caterpillar tracks and can be equipped with different types of sensors and cameras.

What's new about the German pilot project is that it combines a range of specially modified technologies, including adapted ROVs and crawlers, and uses them not just to remove individual bombs, but to quickly clear masses of mixed-up munitions from densely littered sites. These dumping grounds are the legacy of Germany's disarmament. After World War Two, the Allied Forces seized its conventional and chemical weapons, and dumped entire shiploads of grenades, bombs and other munition into the sea.

"For the past 10, 20 years we've been clearing munitions for the purpose of construction – for wind farms, cables, a harbour expansion – and we've always cleared it from areas where there isn't that much to clear, because dumpsites tend to be avoided by those projects," says Dieter Guldin, chief operating officer at SeaTerra, one of the UXO survey and clearance companies participating in the pilot project. "No one's ever said before: 'let's clear munitions for the sake of the environment, let's clear it to clean the sea'. This is a totally new approach."

A key part of this new approach is to "target the dumping grounds, and do it on an industrial scale, working 24/7", he says. "With our current methods, it would then still take 150 years", to clear Germany's waters of munition, Guldin calculates. "The goal for this project is to develop methods that can help us clear the sea within about 30 years."

The first phase of the project, which involves SeaTerra and other specialist companies, will tackle several such submerged piles in Lübeck Bay in the Baltic Sea. They are a fraction of the 400 piles in the bay, but the idea is that the work will yield insights into automating and speeding up the process.

Most of the technologies are already used in offshore projects, Guldin says, but have been adapted for the challenge of tackling the dumpsites, which he describes as a "wild mix" of bombs, mines, grenades, crates of munitions and wrecks.

The tools include an ROV equipped with a camera to survey the seabed from above. Guldin describes it as moving over the seabed, filming munition, which experts on a ship can then see on a screen and identify.

SeaTerra will also use "smart grabbers", a range of differently shaped, sensor-equipped claws attached to cranes on a ship, Guldin says. They reach into the water and grab the munitions gently or firmly, depending on their state – a crumbling crate filled with ammunition may for example have to be scooped up with a grabber that can close into a bowl, he explains.

A crawler will roll across the seabed on caterpillar tracks and pick up objects such as small-caliber ammunition with its smaller grabber, Guldin says. All the grabbers have cameras, allowing the specialists on the ship to look at the munitions on screens.

The smart grabbers then place the munitions into underwater metal baskets, pre-sorting it roughly into one or two types per basket. The ship with the specialists will be staffed in shifts and operate 24-hours a day: "All they do is identify the munition and put it into the baskets, day in, day out," says Guldin.

A crane mounted onto a second ship dips another claw-like grabber into the water to pick up the baskets, and loads the munitions on board where they are cleaned, weighed, photographed and sorted into steel pipes. The pipes are placed onto a chessboard-like, underwater grid on the seabed, with one type of munition assigned to each square, says Guldin.

This careful sorting is important for speeding up the final stage, destruction, Guldin explains. In a later phase of the project, the munition will be loaded into a detonation chamber – a planned huge, oven-like device on an offshore platform – where it is burned: "We can then say, 'ok, for the next two weeks we'll only destroy grenades', and then a ship collects only the pipes with grenades," Guldin says. This is much faster than individually picking and destroying each piece of munition one by one, he says.

The destruction phase is a crucial element of the project, its participants say, as burning munitions is considered more environmentally friendly than blasting – a conventional disposal method, where munitions are basically blown up in the sea. Blasting will not be used in the project. As a disposal method, blasting has attracted criticism for a number of reasons. One is that the resulting noise can harm wildlife such as porpoises. While there are ways to buffer such underwater noise – read BBC Future Planet's feature on using "bubble curtains" to protect porpoises, for example – this still leaves the risk of contamination, experts say.

"When munitions are blasted under water or in the North Sea on sandbanks, which used to be common practice, the toxic explosive isn't completely burnt up but gets spread across the sediment, and washed into the water with the next tide," says Anita Künitzer, senior scientific advisor at the German Environment Agency, which supports the German pilot project.

The first phase of the pilot project in Lübeck Bay is scheduled for July to September this year and will aim to retrieve around 50 tonnes of munitions. The munitions from that phase will be burned in a detonation chamber on land, at a facility operated by GEKA, a company specialising in chemical and conventional munitions disposal.

A deadly catch

The problem of dumped munitions goes far beyond the seabed. Children and beachcombers have occasionally picked up seemingly innocent rocks that turned out to be explosives, or pieces of Baltic amber that turned out to be washed-up white phosphorus from incendiary bombs – which can spontaneously burst into flames when warmed, for example in a human hand, or trouser pocket. Walkers, divers and fishing crews in Europe also continue to find old wartime munitions, with hundreds of encounters recorded by the Ospar Commission, a monitoring body, every year.

Unexploded ordnance can also get in the way of infrastructure projects, including Europe's massive offshore wind farm expansions. (This interactive map shows just how far the planned wind farms stretch across the North and Baltic Sea).

"We've been involved in over 100 wind farms around the world, and we've found unexploded ordnance pretty much on every site," says Lee Gooderham, managing director of Ordtek, a UK-based consultancy specialising in unexploded ordnance risk management. "The legacy of UXOs is not always dump sites, it's mines that have drifted, it's bombs that were dropped in conflict that were not recorded, it's torpedoes that were fired in conflict that missed their target," he adds.

Historical maps may not always be accurate, he says. To create more precise maps that help offshore developers avoid or remove unexploded ordnance, Ordtek uses additional data, for example from drones, but also dispatches researchers to military and historical archives in France, Germany and other countries to find additional records. "World War Two, both the conflict but also training activities, has created the biggest problem" in terms of littering the seabed, Gooderham says, though in its global work the company also deals with the legacy of other conflicts, such as the Vietnam War. Surveys to detect such munitions are a routine part of any offshore infrastructure project, not just wind energy, and increasingly involve technologies such as ROVs, he explains.

Chemical threat

Robots are also helping to investigate another toxic wartime legacy: chemical munitions. Like conventional weapons, chemical weapons were dumped into the sea after World War Two, and have been found to release toxic chemicals.

Ideally, the chemical weapons should be removed from the sea and destroyed in a relatively environmentally friendly manner, says Jacek Bełdowski, a researcher at the Institute of Oceanology at the Polish Academy of Sciences and an expert in dumped chemical weapons. But in practice, "there's just too much of it", he says. "In the Baltic Sea itself, we've got about 40,000 tonnes of chemical munitions. In Skagerrak [near Norway and Sweden] you've got 150,000 tonnes. And in the seas and oceans of the world, there is more… Nobody could recover those amounts and destroy them [in a reasonable amount of time with existing technology]," he concludes.

We still know too little about the risk dumped chemical weapons pose over time, Bełdowski says. "Their degradation is really complex", and also depends on the environmental conditions, he explains. Some become less toxic over time, some become more toxic, and some are stable, he says.

Researchers have studied some of the chemical weapons dumps and their environment, assisted by ROVs. They have also created a decision-making tool to help governments and companies decide what to do with them, case by case. "The next step is to monitor those which are stable at the moment, to check if they are getting worse. And for those which are risky right now, you have to recover and destroy them," he says. That's where, in his view, an industrial-scale process could help.

"This initiative of Germany in Lübeck Bay, which is currently addressing the conventional munitions, would be easily translated to chemical weapons, because lots of the steps are similar," he says, with some additional precautions for chemical weapons, such as perhaps encasing them on the sea floor before lifting them. "You have to safely recover those munitions, without spilling their contents, and then you have to destroy them in high temperature, with the protection of enclosement, and filters."

The German project's priority is to clear the dumps for environmental reasons. But in the long term, Greinert, the scientist, says infrastructure projects such as wind farms could also use the process to dispose of munitions quickly without blasting.

He says one of the most enjoyable aspects of the German project has been seeing the positive public response: "We're really working together on this – society, non-profits, scientists and politicians from across the main parties". His hope is that the result will be lasting change: "We can remove these munitions from German waters, and then they"re's gone, once and for all, and it's not coming back".

-bbc